Assessment of the host range of the white admiral butterfly, Limenitis glorifica Fruhstorfer (Nymphalidae), a biological control agent for Japanese honeysuckle

Introduction

Two closely-related Limenitis spp. occur in Japan. Limenitis camilla japonica (Ichimonji-cho)is widely distributed throughout the Palearctic region, including western Europe where it is called the white admiral butterfly. Limenitis glorifica (Asama-ichimonji), however, is endemic to Japan, where it is widely distributed in Honshu from the western lowlands of Yamaguchi Prefecture to Shimokita Peninsula in the north. In central Japan it occurs up to 1450 m elevation but is normally found to c. 1000 m above sea level and most commonly in the lowlands below. L. glorifica populations generally decline with increasing altitude.

Limenitis glorifica and L. camilla japonica coexist in Japan and both feed on Japanese honeysuckle. Moreover, they are very similar in all life stages although they tend to prefer different habitats. In comparison with the deep forests and valleys preferred by the white admiral (L. camilla), L. glorifica prefers open habitats and willow forest near the banks of rivers. In such places it is often more common than L. camilla. This report summarises what we know about the host plant range of L. glorifica. It examines:

- Historical field observations, early experiments on host range, and recent field observations

- Recent host range tests conducted in Japan and in containment at Lincoln, New Zealand

Field observations and early host range tests

Tanaka (1978) reported that there were L. glorifica host-records from Lonicera japonica, L. caerula var. emphyllocalyx and Weigela coraeensis, but noted that because of the similarities between L. glorifica and L. camilla, confusion regarding host records for these two species in Japan is likely. To investigate the host-ranges of these two butterfly species, Tanaka (1978) performed field surveys and conducted host-range experiments. The field surveys indicated that L. camilla has a relatively broad host-range (feeding on several Lonicera and Weigela spp.) while L. glorifica was almost exclusively found feeding on L. japonica (60/62 records). Tanaka (1978) reported finding one L. glorifica larva on L. morrowii. However, at another site, adult L. glorifica were found flying in the vicinity of L. morrowii, but no eggs were found. Tanaka (1978) reported that, on one occasion, a female L. glorifica was observed to lay a single egg on a Weigela floribunda plant. However, in contrast to the selection of the adult butterfly, the resultant larva did not feed on Weigela floribunda. Tanaka (1978) noted that the Weigela floribunda plant was growing alongside L. japonica. It is possible that oviposition on W. floribunda was stimulated by the presence of L. japonica growing in close proximity.

Host-range tests were performed by Tanaka (1978), using eggs or first instar larvae collected from L. japonica and transferred to test plants or L. japonica controls (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of host-range tests using L. glorifica (Tanaka (1978)

| Plant | Feeding | Pupation | Development to adult |

| Lonicera japonica | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lonicera morrowii | Yes | Yes | Yes, but adults small, wings abnormal |

| Lonicera gracillipes | Yes | No | No, but host-plant quality questioned |

| Weigela floribunda | Nil feeding most reps | 1/10 larvae | One very small adult |

| Abelia spathulata | No | No | No |

Tanaka (1978) found that larvae fed well on Lonicera japonica, L. morrowii, and Lonicera gracilipes (Table 1). However, Tanaka noted that larval growth was retarded when feeding on L. morrowii (compared to L. japonica) and the resultant adults were of small size and expanded their wings imperfectly at the time of emergence. This indicated that L. morrowii is a sub-optimal host. Larvae were not reared to adult on Lonicera gracilipes, but Tanaka (1978) stated that this may have been due to declining host-plant quality (the tests were carried out in autumn and L. gracilipes is deciduous).

Tanaka (1978) stated that, generally, larvae did not feed at all on Weigela floribunda, and for the few that did feed, the developmental period was prolonged and the single adult reared was very small-sized. Larvae did not feed on Abelia spathulata at all.

Subsequently Fukuda et al. (1983) reported that L. glorifica feeding tends to be limited to Lonicera japonica but included additional host records from Weigela decora and Lonicera sempervirens. The record from L. sempervirens was considered exceptional and there is no data to determine the veracity of the host record from Weigela decora.

Both Fukuda et al. (1983) and Tanaka (1978) noted that the distribution of L. glorifica in Japanis limited by the distribution of L. japonica, despite the presence of numerous related plant spp. (17 other Lonicera spp. and 5 Weigela spp. occur in Honshu), which is strong evidence that L. glorifica is a Japanese honeysuckle specialist.

Field surveys were recently conducted in Japan with the aim of collecting L. glorifica eggs from Lonicera japonica plants (Q. Paynter, Landcare Research, pers. comm.). There was limited opportunity to sample other related species, but this limited survey work concurred with previous studies: No L. glorifica eggs/larvae were found on Weigela plants (not identified to species) and Lonicera gracilipes plants growing above Nikko. No eggs were found on Weigela plants growing on the Oshika Peninsula, east of Ishinomaki. Japanese honeysuckle plants growing in dark shady sites were spindly, and only yielded L. camilla eggs and larvae.

Methods

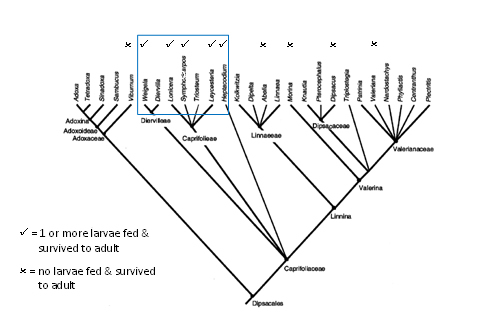

A range of host range tests were conducted at Tsukuba, Japan, and (using imported eggs) in the Landcare Research Insect containment facility at Lincoln, New Zealand in June and July 2012. A total of ten plant species were tested, and the rationale for test plant selection can be found in the Test plant list. The higher classification used was http://www.mobot.org/mobot/research/apweb/orders/dipsacalesweb.htm (accessed November 2012)

Butterflies have complex mating, host plant selection and oviposition behaviours. Limenitis glorifica adults did not mate under laboratory conditions. Testing was therefore largely restricted to first instar survival and development tests. Eggs were collected from Lonicera japonica plants in the field and returned to the laboratory. In the first series of ‘no choice’ tests, a single larva was placed on an excised leaf of each test plant on moist filter paper in a Petri dish. This was repeated 20 times. As far as possible the same size of fragment was used for each test plant. The dish was examined daily for 5 days and then on day 10 to record whether the larva was alive or dead, whether it was feeding, and to visually estimate the intensity of feeding on the foliage provided.

While larvae died within several days on most test plants, some survived on Leycesteria formosa Weigela florida, Symphoricarpus sp.and Heptacodium micanioides. Larvae that survived to beyond 10 days on excised leaf material were transferred to whole potted plants growing in a glasshouse in Tsukuba, Japan. Additional first instar larvae were added, where necessary, to ensure that 10 larvae per plant species were used for the whole potted plant tests. For example, 8 of 20 larvae used in the excised leaf tests on Weigela formosa survived for 10 days and these were transferred to potted plants together with a further 2 first instar larvae so that 10 larvae were placed on whole potted plants. This means that a total of 22 larvae were used in the combined Petri dish and potted plant tests on this test plant species. The fate of these larvae was followed until pupation and adult emergence. Due to time constraints some larvae had to be transported back to New Zealand to complete development in containment at Lincoln. Here larvae were again maintained on whole potted plants in containment until pupation and adult emergence occurred. Pupae were weighed. Adult survivorship after emergence was also followed and recorded.

Results

Almost all control (Japanese honeysuckle) larvae fed normally and survived to emerge as adults. There was no survival on species representing 3 sub-families of the Caprifoliaceae, indicating that the host range lies within that family (Table 2). Lack of survival on Viburnum sp., which belongs to the neighbouring family Adoxaceae, confirms this. However, 4.5% of larvae survived on Weigela formosa, which belongs to the sub-family Diervilloideae so the fundamental, or physiological host range also includes the sub-family Diervilloideae. It is also important to note that within the Caprifolioideae, the fundamental host-range is not restricted to the genus Lonicera, as 26.1% of larvae survived to adult on Leycesteria formosa. Also, not all Lonicera species are susceptible, as the evergreen Lonicera nitida could not support larval development at all.

Table 2. Proportion of first instar white admiral larvae surviving to reach adulthood in no choice tests in Petri dishes.

| Family | Sub-family | Test species | No. survived 10 days in Petri dishes | No. survived to adult in potted plant tests | Total No. larvae used in tests | % survival to adult | |

| Caprifoliaceae | Caprifolioideae | Lonicera japonica | 18/20 | 9/10 | 20(10) | 81.0 | |

| Lonicera nitida | 0/20 | - | 20 | 0.0 | |||

| Symphoricarpus sp. | 10/20 | 1/10 | 20 | 5.0 | |||

| Leycesteria formosa | 7/20 | 6/10 | 23 | 26.1 | |||

| Heptacodium micanoides | - | 1/10 | 10 | 10.0 | |||

| Diervilloideae | Weigela formosa | 8/20 | 1/10 | 22 | 4.5 | ||

| Linnaeoideae | Abelia sp. | 0/20 | - | 20 | 0.0 | ||

| Morinoideae | Morina longifolia | 0/20 | - | 20 | 0.0 | ||

| Dipsacoideae | Dipsacus sylvestris | 0/20 | - | 20 | 0.0 | ||

| Valerianoideae | Valeriana officinalis | 0/20 | - | 20 | 0.0 | ||

| Adoxaceae | Viburnum sp. | 0/20 | - | 20 | 0.0 | ||

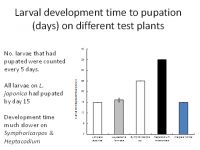

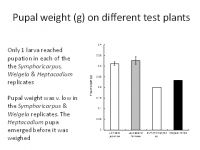

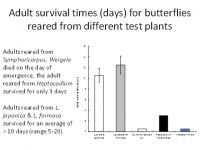

To be ecologically fit, an individual must not only complete its development but be long-lived and fecund. Larvae reared on Symphoricarpus sp and Heptacodes micanoides took longer to complete development than those fed on Lonicera japonica and Leycesteria formosa (Figure 1) and produced smaller pupae (Figure 2). Pupa weight is often used as an indicator of lifetime fecundity. Similarly, whereas larvae fed on Lonicera japonica and Leycesteria formosa produced adults that survived for approximately 10 days, those fed on other hosts produced adults that died almost immediately (Figure 3). Thus, although the physiological host-range of L. glorifica might include plants other than L. japonica, the ecological host range is much narrower.

Figure 1. Time taken for larvae to pupate when fed on a range of tests plants.

Figure 2. Weight of pupae resulting from surviving larvae when fed on a range of test plants.

Figure 3. Adult lifespan of butterflies reared as larvae on a range of host plants.

Adult butterflies did not mate in quarantine conditions, but female butterflies laid infertile eggs regardless. It was noted that there was a strong (~5-fold) preference for oviposition on L. japonica over L. formosa and W. Florida. If this pattern held for deposition of fertile eggs, it would provide additional evidence that these species are less acceptable host plants for L. glorifica. This remains uncertain.

Discussion

The results of the field surveys and early host-range tests in Japan suggested that the host-range of L. glorifica was confined to the sub-family Caprifolioideae of the Caprifoliaceae (and, potentially, from the sub-family Diervilleoidae), and that it was probably a Lonicera japonica specialist. Indeed, Tanaka (1978) stated that the distribution of L. glorifica is limited in some regions of Japan by the lack of Lonicera japonica. There are no host records of L. glorifica from most of the other seventeen Lonicera spp. that occur in Honshu (http://foj.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/gbif/foj/), and no host records from Triosteum sinuatum and T. pinnatifidum (sub-family Caprifolioideae), which are both naturalised in Japan.

There are no host-records from most Weigela spp. (sub-family Diervilloideae) that occur in Honshu, and those few confirmed records (e.g. Tanaka, 1978) indicate that Weigela is a sub-optimal host plant for L. glorifica and eggs are only rarely laid. There are no host records from Abelia spp. and Linnaea borealis (sub- family Linnaeoideae), which are also native to Japan.

The related family Adoxaceae is represented in Japan by the genera Adoxa, Sambucus and Viburnum. There are no records of L. glorifica on any plant species belonging to these genera.

Limenitis spp. are familiar butterflies in Japan and there are a large number of amateur entomologists there. L. glorifica is very common at some sites (dozens of eggs can be collected in a relatively short period of time), so if attack on other Lonicera or Weigela spp. was occurring it would almost certainly have been noted. A formal survey also failed to find significant attack on other species (Tanaka, 1978).

There appears little doubt that the two Limenitis spp. are confined to Weigela and Lonicera, so the absence of Japanese records from Adoxaceae and other Caprifoliaceae are very reliable. Akihiro’s entomologist colleagues at NIAES are convinced that L. glorifica is a L. japonica and ‘open habitat’ specialist. L. glorifica is replaced by L. japonica in dense forest (Q. Paynter, Landcare Research, pers. comm.). It is highly unlikely that populations of L. glorifica will persist on Weigela, but some minor spill over might occur. Clearly the evergreen honeysuckle L. nitida is unsuitable (which means L. pileata, which is also evergreen with tough leaves, is probably unsuitable too). Despite the similarities between L. periclymenum and L. japonica, they are in different sub-genera (sub-genus Caprifolium and sub-genus Lonicera, respectively), so it would not be surprising if L. glorifica is not attracted to/performs less well on L. periclymenum, but that is conjecture.

The host-specificity implied by field observations and literature records was strongly supported by the results of host-range experiments. We can conclude that:

- The fundamental or physiological host range was confined within the family Caprifoliaceae

- Larvae placed on test plant species belonging to the sub-families Linnaeoideae, Morinoideae, Dipsacoideae, or Valerianoideae did not survive

- Larvae placed on Weigela (sub-family Diervilloideae) mostly died, but of the 10% that survived, development time was extended, pupal weight was low and adult survival was short, all indicating that this is not an acceptable host plant for the white admiral.

- L. glorifica will have a narrow host range in New Zealand, confined to species in the sub-family Caprifolioideae

- Not all species in this sub-family are hosts. Three of the five plants tested did not provide adequate nutrition for the white admiral.

- Moderate survival on Leycesteria formosa indicates this weedy species may be a suitable host for L. glorifica in New Zealand

- The potential host range for L. glorifica in New Zealand will be narrow, but we cannot exclude the possibility that some untested ornamental Lonicera spp. that lack tough foliage (e.g. L. periclymenum) may be suitable host plants.

References

Fukuda H, Hama E, Kuzuya T, Takahashi A, Takahashi M, Tanaka B, Tanaka H, Wakabayashi M, & Watanabe Y. 1983. The life history of butterflies in Japan Vol. II. Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese with English summary).

Tanaka B. 1978. Larval food-plants and distribution of Japanese Ladoga (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Trans. Lep. Soc. Jap. 29, 35-45.