How ancient DNA can help restore our biodiversity

Like other remote archipelagos, New Zealand’s flora and fauna had many endemic species – found nowhere else – before human arrival.

Since then, more non-native species have been introduced and naturalised than almost anywhere else in the world except Hawaii. About half our flora are made up of naturalised non-native plant species, and with the extinction of more than 50 native land birds since human arrival there has also been a shift from a bird-dominated to a mammal-dominated fauna.

At Manaaki Whenua’s Long-Term Ecology Laboratory, we study longterm ecological processes (over decades to thousands of years) to help understand the dynamics, function, and trajectories of present-day ecosystems and to inform their restoration.

Gallery

A tarsometatarsus (lower leg bone) of the extinct Finsch’s duck (Chenonetta finschi) found at Walter Peak Station, near Lake Wakatipu.

Drs Jamie Wood and Janet Wilmshurst (right) search for coprolites on a field trip near Mt Nicholas Station, Lake Wakatipu, Otago.

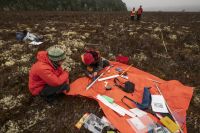

Dr Jamie Wood from Manaaki Whenua talks with feature writer Kate Evans (right) as the field team search for coprolites.

Collecting wetland sediment core samples on the Kepler Track.

The core sample is checked after being extracted.

Because New Zealand was settled so recently compared with many places on the planet, and at a time when climates were similar to today, pre-human ecosystem and species baselines are highly relevant to help inform current conservation issues.

For example, pollen and ancient DNA (aDNA) analyses of kākāpō coprolites (fossilised droppings) from Honeycomb Cave in NW Nelson have revealed these enigmatic threatened parrots once played a role as pollinators of the now endangered endemic parasitic flowering plant Dactylanthus, the wood rose. Until this revelation, it was thought that only native bats were pollinators of this strange plant; our improved understanding of ecosystem dependencies such as these is a significant contribution to species conservation and may help expand options for where both species might survive in the future.

In other work, our team’s recent estimations of pre-human moa population densities, and their diets derived from coprolite analyses, will help us better understand and manage current pressures on native forest plant species following the replacement of moa in our landscapes by other herbivore browsers such as deer. Another ongoing study is a Marsdenfunded project focused on the analysis of kiore (Pacific rat) coprolites found in New Zealand, which will help us define the impact of New Zealand’s first naturalised invasive mammal on pristine island ecosystems.

New Zealand’s offshore island reserves offer some of the best opportunities to restore and preserve native biodiversity. Deciding how to restore these reserves can be assisted by reconstructing their past states. For example, a recent project reconstructing the vegetation history of Tawhiti Rahi (Poor Knights Islands) using pollen and aDNA analyses revealed an interesting surprise. The currently native pōhutukawa-dominated forest, thought to be a climax forest type, is actually just a successional forest that established when a 550-year human occupation on the island came to an end. Before human occupation, the vegetation was dominated by a diverse range of angiosperm and conifer species and palms. Given that forested islands like Tawhiti Rahi have been used to help guide the restoration and revegetation of other degraded offshore islands, it is clear how our study of the past offers a useful tool to inform restoration.

Our research continues to turn up ecological surprises and, importantly, shows how the past can generate new insights that are directly relevant to the conservation and restoration of present-day ecosystems and species interactions.