Pacific colonisation more recent and rapid than earlier thought

New research shows early human colonisation of East Polynesia was much faster and more recent than previously proposed, providing a robust new timing and sequence for the colonisation of the region.

Thursday 28 Oct 2010

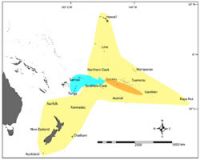

Islands of East Polynesia, summarizing the two phases of migration out of West Polynesia (blue shading): first to the Society Islands (and possibly as far as Gambier) between A.D. ∼1025 and 1121 (orange shading), and second to the remote islands between A.D. ∼1200 and 1290 (yellow shading).

New research shows early human colonisation of East Polynesia was much faster and more recent than previously proposed, providing a robust new timing and sequence for the colonisation of the region.

Polynesians colonised the region in two distinct phases: earliest in the central Society Islands (AD 1025-1120, four centuries later than previously assumed); then between 70 and 265 years later, dispersal continued in one major “pulse” to all remaining islands - including New Zealand, Hawai’i and Easter Island between ~AD 1200 and 1290.

The findings have just been published in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States and mean existing models of human colonisation, ecological change and historical linguistics for the region now require substantial revision.

The study was based on an analysis of over 1400 radiocarbon dates from 47 islands in the region.

“This is an amazing feat of Polynesian sea voyaging and discovery, and represents a rate of dispersal unprecedented in oceanic prehistory,” said lead researcher Dr Janet Wilmshurst.

“It’s even more incredible given that these isolated islands are spread across a vast area of the Pacific Ocean from the subtropics to the subantarctic. Nearly all of the 500 or so islands were discovered, despite being scattered across an area of ocean the size ofNorth America.”

In the last prehistoric expansion of modern humans, Polynesians from the Samoa-Tonga region dispersed throughout the remote islands of East Polynesia. This cultural region includes New Zealand, the Chathams (Rekohu), Auckland Islands, Norfolk Island, the Kermadecs, Society Islands, Cooks, Australs, Gambier, Tuamotus, Marquesas, Line, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) and Hawai’i. The timing and sequence of this remarkable event have been highly debated and poorly resolved, precluding the understanding of cultural and ecological change that followed.

The work resolves longstanding paradoxes and offes a robust explanation for the remarkable uniformity of East Polynesian culture, human biology and language, Dr Wilmshurst says.

Co-author Professor Atholl Anderson said the team chose an objective “top-down” approach to evaluate the entire archaeological radiocarbon database for East Polynesia as a single entity.

“This allowed all radiocarbon dates, irrespective of their context within an archaeological deposit, to be categorised according to their reliability to provide an accurate and precise age for initial colonisation on each island,” Prof. Anderson said.

The study sorted all radiocarbon-dated materials into sample type including categories of short-lived plant remains (such as seeds or small twigs), unidentified wood charcoal, bone and marine shells.

Co-author Dr Carl Lipo said because short-lived plant remains are the least likely sample material to suffer from contamination or calibration issues, and most likely to date an event accurately and precisely, these were selected as a subset of reliable dates from which estimates for the age of initial colonisation were made.

“The results showed than none of the radiocarbon dates on reliable short-lived plant materials were older than ~ AD 1000. This contrasts with dates on other material types that extend back to c. 350 BC,” Dr Lipo said.

Another co-author, Prof. Terry Hunt, said unidentified charcoal, bones and marine shell contain a substantial risk of error associated with them which can make the age of the sample appear older than it really is.

“These are the very materials commonly used by some researchers to date the age of an archaeological site and to support longer chronologies,” Prof. Hunt said.

“As the probability of just one type of sample material providing only younger radiocarbon dates is low, our new results are robust and objective,” Prof. Anderson said.

“It has been nearly 20 years since the last appraisal of the timing and pattern of initial human colonisation in East Polynesia. Now we have more than ten times the number of radiocarbon dates available to us, and from a larger number of islands, so the time was ripe for a new and rigorous, systematic analysis,” he added.

Dr Wilmshurst said the new pattern and timing of colonisation has important implications for interpreting and understanding the colonisation process of East Polynesia.

“For example, migration into the region began after an 1800-year pause since the first settlement of Samoa about 800 BC, implying a rapid onset of whatever cultural or environmental factors were involved. Perhaps these were rapid population growth, technical innovation in sailing vessels that removed distance as a barrier to long-range voyaging, climate or environmental disaster.”

Prof. Hunt said the remarkable similarities in artefacts documented in the “archaic East Polynesian” assemblages of the Societies, Marquesas, New Zealand, and other islands reflect homology of forms (e.g. in fishhooks, adzes, and ornaments) with late and rapid dispersals over the region.

“Similarities of form attributed to continuing interisland group-contacts may actually reflect sharing that occurred in mobility associated with colonisation and not a later phase of long-distance interactions,” he added.

Prof. Hunt said linguistic similarity, often used to trace relationships of populations in East Polynesia according to a longstanding model of relatively slow, incremental expansion, now needs to be reconsidered.

Later colonisation now shortens the time frames of human impacts on island ecosystems, particularly deforestation, and plant and animal extinctions.

Environmental transformations may have occurred over decades rather than centuries and include impacts on both terrestrial and marine biota caused by humans hunting; predation by introduced animals such as the Polynesian rat, dog, and pig; as well as the human use of fire within the short occupational chronology they propose.

“Whereas species declines were thought to have occurred over a thousand years or more, it now appears that in most cases several hundred years was all it took,” said Dr Wilmshurst.

Some researchers have suggested that there was a long period of relatively benign interaction between humans, rats, dogs and pigs and indigenous vertebrates. These views now need revising, as the new model of colonisation chronology suggests impacts had to have been immediate, severe and continuous.