Native forests & shrublands as a place to store carbon

Few of us now doubt the reality of climate change, or the contribution our increasing use of fossil fuels is making to atmospheric warming. The question is what to do about it. New Zealand’s response has been to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, which commits us to reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2012. Included in that agreement, which became legally binding in early 2005, is a requirement to establish systems to monitor the sources and sinks of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. For carbon dioxide, which is removed from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and stored as wood1, this requires the ability to measure and report on carbon storage in our forests and shrublands.

Few of us now doubt the reality of climate change, or the contribution our increasing use of fossil fuels is making to atmospheric warming. The question is what to do about it. New Zealand’s response has been to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, which commits us to reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2012. Included in that agreement, which became legally binding in early 2005, is a requirement to establish systems to monitor the sources and sinks of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. For carbon dioxide, which is removed from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and stored as wood1, this requires the ability to measure and report on carbon storage in our forests and shrublands.

Over the last five years staff from Manaaki Whenua, Ensis (a joint venture between Scion, formerly Forest Research, and CSIRO), and Wildland Consultants have been measuring the amount of carbon stored in native forests and shrublands throughout New Zealand, and whether this is increasing or decreasing. With the first phase of the project nearly completed, some interesting results are beginning to emerge.

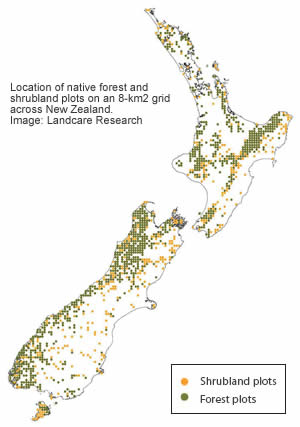

Estimating carbon storage requires a knowledge of the areal extent of forest and shrubland vegetation, and the average amount of carbon (tonnes/ha) stored in that vegetation. The former is obtained from maps derived from satellite photography (which are currently being updated) and the latter from a network of c.1300 permanent plots on an 8-km2 grid across New Zealand. Wherever a grid intersect falls within an area mapped as forest or shrubland, field teams establish a permanent plot, using a standard methodology for biodiversity plots with additional measurements to enable the calculation of carbon stocks. The plot network has taken 5 years to establish, and will be remeasured between 2008 and 2012 to determine the extent of changes taking place.

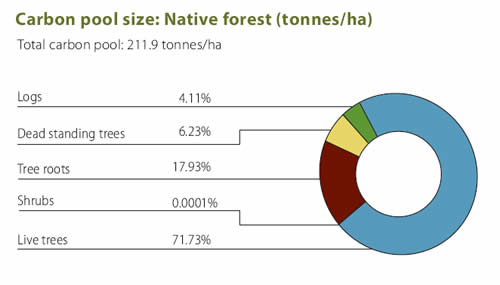

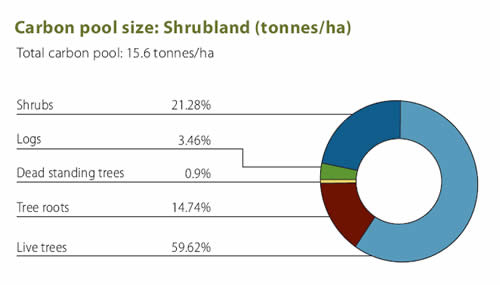

Analysis of the data over the past year shows that while New Zealand has several hundred tree and shrub species, only a few (including the beeches, kāmahi, rimu, tawa, southern rātā, kānuka and broadleaf) are widespread and common, and it is these species that store the bulk of the carbon. Similarly, when it comes to storing carbon it is the size of the trees rather than how many there are that matters. Carbon storage averaged 211.9 ± 20.3 tonnes/ha in native forests and 15.6 ± 6.6 tonnes/ha in shrublands5, about 90% of which was contributed by the live trees and shrubs. These figures closely parallel earlier local or regional estimates.

|

|

The use of a biodiversity-based methodology also opens up exciting opportunities for researchers and managers to examine and report on changes to indigenous forests and shrublands at a national scale, something we have not been able to do before. While the biodiversity data have not yet been analysed in detail, they have already yielded at least one new species of liverwort and another that was not previously known from New Zealand.

One opportunity to help meet Kyoto targets is to establish permanent forest on former grasslands. It also provides carbon credits for the landowners.

Carbon farming opportunities for Māori land

We have identified about 200,000 ha of “Kyoto eligible” Māori land nationally. The Gisborne–East Coast region, selected for more in-depth study, shows at least 50,000 suitable hectares.

This research has identified the incentives, such as economics and Māori values, needed to adopt carbon farming practices nationally.

Our researchers, along with a PhD student from Stanford University, USA, are gauging the level of interest from Māori landowners throughout the country. Findings show strong support in principle, but wariness of taking up Government incentive schemes that do not consider Māori land structures, governance, values, and issues.

By taking Māori concerns into account, work is progressing to develop “culturally based” carbon contract models.

He mea tauhou tēnei, arā, te pāmu waro, ēngari kei te tirohia e ētahi iwi mehemea he pai, kāre rānei, tēnei momo mahi ahuwhenua. E kī ana, o ngā whenua Māori katoa o te motu, e rua rau mano heketā ka taea te pāmu pēnei. Na te aha? Na te mea he ōrite ki ngā tikanga Māori e pā ana ki te whenua, ā, kua kitea noa atu te wāriu, arā, ngā rawa ka maringi mai. Ko ngā iwi o Te Tairāwhiti kei mahi tahi me Manaaki Whenua kia kitea ai mena he huarahi pai tēnei hei haeretanga.

1Wood is approximately 50% carbon

2Excludes carbon stored in the soil