How Much Do Biocontrol Projects Cost?

Being able to predict the cost of a weed biocontrol programme is an important part of improving the prioritisation of targets and success of projects.

“Super sleuth” Quentin Paynter has been busy delving into the archives again, but this time focusing on which factors influence the cost of biocontrol programmes the most. Quent looked at the following key factors:

- Opposition to controlling a particular weed because of its perceived economic or ornamental value

- Taxonomic isolation relative to native New Zealand plant species

- Whether the project type was ‘novel’ or had already been attempted overseas for the same weed target.

“In total we reviewed the information for 43 weed biocontrol agents released between 1972 and 2013 in New Zealand and which had been subjected to stringent host-range testing prior to their release,” explained Quent. “This information was sourced from Landcare Research databases and comprised projects funded by all sources, including the National Biocontrol Collective and the Ministry for Primary Industries’ Sustainable Farming Fund,” he said.

Quent compiled a comprehensive list of costs associated with each agent released, as well as a list outlining the cost of biocontrol programmes for specific weed targets in New Zealand. By summarising the information in this way it became apparent that opposition to specific biocontrol programmes did not contribute greatly their cost. There were only a few examples where opposition significantly delayed and affected the programme cost. “These days, we conduct a feasibility study prior to a programme commencing and would always ensure that conflicts of interest are resolved before embarking on a project,” said Quent. This would often include a comprehensive cost–benefit analysis in the early stages, and the project would only proceed when the costs of the weed (both economic and environmental) outweigh the desired attributes.

Taxonomic isolation of the weed was surprisingly not a strong predictor of the cost of releasing agents against weeds either. “Despite host-range testing being more complex and time consuming when the target weed is more closely related to native New Zealand plants, taxonomic isolation did not greatly influence the cost of the programme,” said Quent. This suggests other factors are more important. “Certainly disease can inflate the cost of projects hugely,” said Quent. For example, the three beetles selected to control tradescantia (Tradescantia fluminensis) were infected with gut parasites that were difficult to eliminate. Individual eggs had to be painstakingly sterilised and line-reared for many months before disease-free populations were achieved that were suitable for release. Clearing the beetles of disease was estimated to cost around NZ$200,000 for each species, or an additional NZ$600,000 all up.

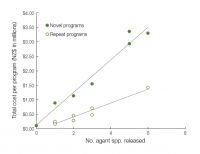

Programme type was a strong predictor of cost. Where a programme used agents that had already been developed for release overseas, not surprisingly programme costs were cheaper – nearly four times less (c. NZ$0.5 million) than projects starting from scratch with new (or novel) agents (c. NZ$1.9 million). There was also a strong correlation between programme cost and the number of agents released (see graph). This suggests that there could be savings if agent selection was improved so that fewer, more effective agents are released. This means that sometimes it might be better to wait and see how agents released overseas perform before introducing them to New Zealand.

This study reinforces that weed biocontrol agents developed in New Zealand have been extremely cost-effective compared with other countries with much bigger budgets. The average cost of developing an agent for New Zealand was NZ$355,686 (with the average cost per novel agent being NZ$475,334, more than double the average of NZ$202,803 for repeat agents). By comparison in 1997 the cost on average to produce a weed biocontrol agent overseas (based on the number of scientist years to test an agent reported by practitioners in Canada, Europe and the USA) through to introduction was estimated to be US$460,000. This equates to approximately NZ$1 million in 2014 (taking into account the exchange rate of the day and CPI adjustment). “With a growing number of weeds to target and limited funds, we will to continue to identify where savings can be made without compromising safety or efficacy,” concluded Quent.

Paynter QP, Fowler SV, Hayes L, Hill RL 2015. Factors affecting the cost of weed biocontrol programs in New Zealand. Biological Control 80: 119–127.

This project was funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment as part of Landcare Research’s Beating Weeds Programme.