Feasibilty of Biocontrol for Evergreen Buckthorn

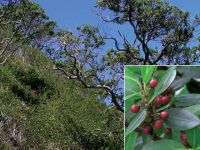

Evergreen buckthorn on Motukaha Island. Image - Auckland Council

We were recently approached by Auckland Council (AC) to take a look at biocontrol options for evergreen buckthorn (Rhamnus alaternus), which is threatening coastal and offshore island native plant communities. This is another species that originates from North Africa, Asia, the Mediterranean and parts of Europe, but its weedy threat has been largely overlooked in the past because it has spread slowly relative to other plant pests.

Evergreen buckthorn is an attractive ornamental plant with, as its name suggests, thorns, and small, green, fragrant flowers that are pollinated primarily by insects. Once pollinated, the plant produces poisonous red berries. When ripe, the berries become attractive to birds, which transport the seed to new places.

“Rhamnus is a major weed of the inner Hauraki Gulf and we have an active control programme on Waiheke and Rakino Islands but it is often difficult to access the plants unless you have abseiling equipment,” said Holly Cox, who is a senior regional advisor for plant biosecurity at AC. “DOC is also managing the weed on Rangitoto and Motutapu Islands. But the problem is that it grows abundantly in people’s gardens along the coast of the Waitemata Harbour on the North Shore and eastern suburbs, which means that the birds can easily bring the seeds over to the islands,” Holly said. “We are looking at biocontrol as an option because in places it is really dense, dominating coastal cliff habitats, altering the ecology and limiting the opportunities for native plant recruitment,” Holly added.

Evergreen buckthorn can also be found in a number of other places around New Zealand from Northland to Otago, so it is very adaptable, growing at a range of altitudes and latitudes. The plants are drought tolerant, with a persistent seed bank that germinates quickly following fire, and are also frost resistant. These are all characteristics of competitive, invasive plants,” said Ronny Groenteman, who has been leading the feasiblity study.

“In northern Spain, which has a similar climate to New Zealand, evergreen buckthorn grows from sea level to altitudes of 1300 m,” Ronny said. “There are several things that make evergreen buckthorn a good target for biocontrol, such as having no closely related indigenous species in New Zealand and not being a favoured ornamental plant. Also, it is a difficult plant to control using herbicide because it grows amongst native plants that are susceptible to the same chemicals. This is one of the main reasons that biocontrol is potentially the only cost-effective option for this plant in the longer term,” Ronny confirmed.

Biocontrol has been explored overseas for two other closely related buckthorn species, R. cathartica and Frangula alnus, which have become invasive in North America. However, because that part of the world has closely related native plants, no insect agents could be found that were sufficiently host-specific to use as biocontrol agents. Plant pathogens may yet offer some hope down the track. Several fungal pathogens have been isolated from Rhamnus species that could be possible candidates.

With respect to evergreen buckthorn, fourteen species of host-specific insects and one rust fungus have been reported in the literature, and dedicated surveys may well reveal more natural enemies. The potential of the pathogen and at least eight of the insects (including five species of psyllids, two butterflies and a gall midge) appear to be worth examining further.

Ronny considers evergreen buckthorn to be an ‘intermediate’ target in terms of predicting biocontrol impact but warns that it would likely be a relatively expensive target, given that the project would have to start from scratch. For such projects the cost of developing biocontrol agents is historically on average $475,000 per agent, and generally 2–3 agents are needed.

Ronny has identified a number of useful next steps. These include undertaking a baseline survey of natural enemies already present in New Zealand on evergreen buckthorn, including organisms that might disrupt a biocontrol programme, and a molecular study to pinpoint the exact geographic location that the New Zealand material originated from in order to inform native range surveys for potential agents. Another useful step would be to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of how different control options compare, including a ‘doing nothing’ approach. Ideally, this would consider future weed spread scenarios and include the economic impact of controlling the weed on offshore islands in the Hauraki Gulf that are managed as wildlife refuges.

This feasibility study was funded by Auckland Council.