Comparing Ragwort Then with Now: Part One

Ragwort

In a world where accountability and measurable outcomes are becoming the norm, there seems to be more need than ever to demonstrate whether a project has been successful or not. “We have the techniques to monitor the impact of weed biocontrol agents in detail, but such work tends to be very expensive and therefore unable to be undertaken very often,” said Simon Fowler, who leads the Beating Weeds research programme. “Since this has proven to be a barrier to following up on the success of weed biocontrol programmes, we have been developing more cost efficient methodologies that can use to achieve the same endpoint.”

An approach trialled recently has been to revisit ragwort flea beetle (Longitarsus jacobaeae) release sites nationwide, 20–30 years after the beetles were released, and collect some simple information about the status of ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris) on these properties now. The ragwort flea beetles were released at sites with significant ragwort problems, often 10–20 large plants/ m2. “We know that the flea beetle has had a big impact on the ragwort, because it is clearly nowhere near as prevalent as it used to be, but hard data is needed to support our observations,” explained Simon. The strength of this assessment approach is the potentially large number of sites (>100) that data can be gathered from nationwide. While this data only provides a correlation (suggestion of a cause-and-effect relationship), it contributes to the overall story, supporting the cause-and-effect data that has been collected at a few sites through insecticide exclusion studies (where some ragwort plants were protected through the use of insecticide). It also enables people to compare results in their region with nationwide trends.

Landcare Research has an extensive database that summarises all known information about where biocontrol agents they provided have been released and their fate. From the >100 ragwort flea beetle release sites a list was drawn up of those that regional council staff would be asked to attempt to revisit. Sites that were known to have been destroyed were excluded, as were those for which there was no estimate of ragwort density around release time to use as a comparison. Although ragwort density was not always recorded when the flea beetles were released, density was estimated each time sites were subsequently revisited, so for many sites this data was available 1–3 years after the beetles were released and before they would have begun to make a serious dent in the ragwort.

Initially the approach was trialled as a pilot in three regions during 2011 and 2012: Wellington, Manawatu–Wanganui and Waikato. Site were visited at least twice in autumn (consistent with other monitoring), and in different calendar years to reduce the impact

of any unusual annual variation that can occur with this plant. After the pilot trial the survey methodology was fine-tuned and then rolled out nationwide. “It proved more difficult than expected for regional council staff to fit in the site checks, which meant it took 4 years instead of 2 to collect this more extensive survey data,” said Lynley Hayes, who helped to organise the survey. All up just over 70 sites nationwide were able to be resurveyed. Given the time elapsed since the releases, it was unusual for the same people who made the original releases to be involved in this survey, once again emphasising the need for good record keeping. A considerable number of the properties visited had also changed hands, with many landowners unaware of the flea beetles and their contribution to ragwort control.

The survey asked landowners questions about the management of the land, such as the farming type (e.g. dairy cows, beef stock, sheep, deer or horses) to see if that made any difference to the results, and any ongoing ragwort control efforts. They were also asked to describe the biocontrol programme in three words. We will report on these aspects of the survey results in the November issue of this newsletter. As well as questioning the landowners, the regional council staff visually estimated the density of ragwort remaining at the sites as well as checking for the presence of the beetle and other ragwort biocontrol agents. Photos of release sites were requested, but it proved difficult to take ‘after’ shots that lined up well with ‘before’ shots, due to a lack of data about where the original photos were taken or changes to landmarks (such as trees), in the interim. But the numerous photos of clean pasture still contribute to the overall story.

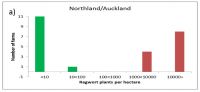

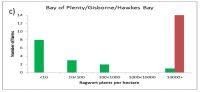

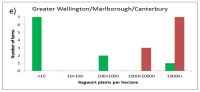

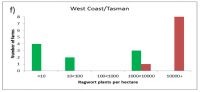

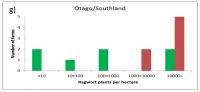

The data show that ragwort density has declined enormously since the release of the ragwort flea beetle (see graphs). At 42% of the sites there was no ragwort evident at the time the sites were checked, and at 51% of sites ragwort had declined by 90–99%. However, in 7% of the sites there had either been less than a 50% reduction in ragwort density or even an increase in density. Reductions in ragwort density occurred all over New Zealand, but the effect was strongest in the northern regions, which is consistent with previous information suggesting that ragwort declines were less dramatic in cooler or very wet regions, such as the West Coast and Southland.

The survey also showed that high numbers of the ragwort flea beetle were found at sites with mean annual rainfall up to 2000 mm. This is consistent with previous data that suggests the flea beetle larvae don’t like getting too wet. However, the threshold of around 2000 mm/yr is encouragingly higher than that shown previously (1670 mm/yr), indicating that the flea beetle is able to do well in somewhat wetter regions than was previously thought.

The number of release sites in five ragwort density categories: before biocontrol had any effects (red bars) compared to the recent reassessments (green bars)

Northland & Auckland

Waikato

Bay of Plenty/Giborne/Hawkes Bay

Taranaki/Horizons

Greater Wellington/Maroborough/Canterbury

West Coast/Tasman

Otago/Southland

Cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae) was encountered at 68% of ragwort flea beetle release sites at some stage over the course of the study and is well spread throughout New Zealand. However, its occurrence at damaging levels was only ever noted sporadically, and earlier studies have shown it to be limited by natural enemies.

The study also found the ragwort plume moth (Platyptilia isodactyla) present at seven sites. On the West Coast the plume moth has self-colonised at least three of the ragwort flea beetle release sites, including the wettest site in the study (Whataroa, with a mean annual rainfall of 5305 mm). The fact that the plume moth is dispersing to new sites on the West Coast means that, as intended, it is doing well in these areas that are too wet for the flea beetle. The data also suggests that the plume moth may already be causing some declines in ragwort at these wet sites, again supporting other observations of the impact of this agent.

To summarise, the objective of this project is to develop simple, yet powerful, methods that can be used to demonstrate whether a biocontrol programme has been successful or not. This project has achieved that aim, capturing vital information from a wide geographic range and showing regional differences in agent performance. “By involving many people we have been able to share the load and collect meaningful data in a highly cost- effective manner without imposing a huge burden on any one party,” concluded Simon. A similar resurvey project is underway to study the impact of nodding thistle (Carduus nutans) agents. A pilot study for this has been completed and the project will be rolled out nationwide this spring.

This project was funded and data for it was collected by the National Biocontrol Collective. A huge thanks to everyone who contributed to this survey!