Camera trapping and occupancy models to measure residual stoat populations

In pest control, it isn’t the number of animals you remove that matters. It’s the number that remain. Monitoring the level of these residual pests in controlled areas is vital to the optimisation of trapping regimes and to determine whether each programme is meeting its pest reduction goals. In order to do this, conservation managers need reliable, accurate, and timely measurements of the abundance of their target species.

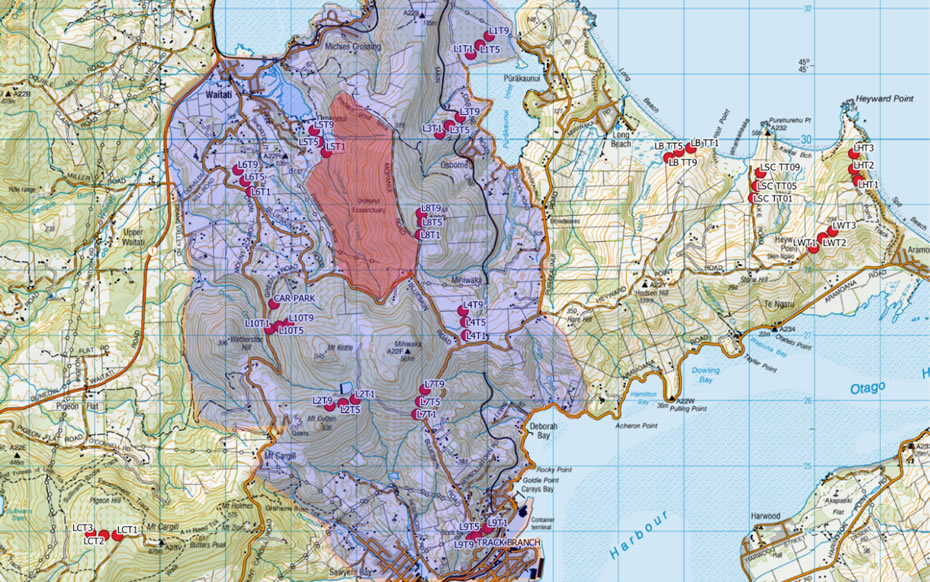

Predator Free Dunedin hopes to remove >90% of stoats within the Halo region, an unfenced but highly trapped area surrounding the Orokonui pest-free sanctuary north of Dunedin. This ambitious reduction in stoat abundance should result in significant ecological benefits, but how do you measure stoat population density? There is no standard measure of stoat abundance, and all mustelids are cunning and cryptic, making them difficult to detect. When stoats invaded Kapiti Island they were undetectable using baited tracking tunnels, and currently very few stoats are detected within the Halo region using these methods. Baited camera traps have been suggested as a way to measure stoat abundance, but the ideal number and distribution of cameras, and the statistical power of these networks to detect population changes, requires investigation and refinement.

Each camera was focused on a lure of fresh rabbit meat, Erayz lure, and ferret bedding lure, a mixture particularly attractive to stoats. Each camera was set to record three photographs in succession when triggered by movement, allowing each animal to be identified to the species level. The researchers then created indices of abundance for each species based on the number of encounters per 1,000 camera hours, and did spatially and temporally related occupancy modelling for the target species. Occupancy modelling uses repeated observations, either through spatial replication (multiple cameras close to each other) or temporal replication (the number of time periods in which a species was detected versus time periods without detection) to assess both the detectability of each species, and the proportion of the landscape occupied by the species. This kind of modelling can discern whether low detection rates are because of low species abundance or difficulty in detecting a species even when it is present.

Over 70,000 photographs were taken during the study period, with some cameras taking more than 6,000 images and others taking only hundreds. Over 1,000 encounters with animals were recorded by the cameras; encounters were defined as detections separated by at least 30 minutes from previous detections of that species at that site. This filtering process removed repeated photographs of individuals foraging around the camera. Rats were the Figure 1:most recorded pest species (303 encounters), with cats the most encountered carnivore (48 encounters), then stoats (15 encounters), ferrets (13 encounters) and weasels (one encounter). Stoats were more active during the day, but were also recorded at night.

Rabbits, hares, possums, mice, pigs, goats and sheep were also detected. Birds were encountered 278 times, including several endemic species such as bellbirds, rifleman, kākā, and tomtits, along with some Australasian harrier hawks that tried to eat the rabbit lure.

Rabbits, hares, possums, mice, pigs, goats and sheep were also detected. Birds were encountered 278 times, including several endemic species such as bellbirds, rifleman, kākā, and tomtits, along with some Australasian harrier hawks that tried to eat the rabbit lure.

Pleasingly, bird encounters were significantly more common in the Halo region than outside it. Occupancy estimates for each pest species (which varied depending on the parameters used) were stoats 56–99%, ferrets 34–39%, cats 63–70%, rats 85–95%, mice 80–90%, and possums 69–87%. The reason why few stoats were encountered despite the high occupancy estimates is that even where stoats are present, there is a low probability of them being detected by a camera on a given night, despite the best-practice lure being used, because the population density is low compared to that of other species, and the home ranges are comparatively large.

All cameras placed in grassland had frequent false triggering due to grass movement in the wind, shadows, and interference by livestock. The camera memory cards became filled with these images, limiting the collection of usable data. No mustelids were detected by cameras in grassland (although they were detected on cameras placed in small bush patches adjacent to farmland). The extremely high numbers of false triggers in open grassland settings, along with the lack of mustelid detections in these settings, indicate that cameras are not an effective tool for mustelid detection there. Additional expense is incurred in the time required to process the images.

From this study, Andrew Veale and his colleagues found that camera trapping is a viable method for monitoring mustelid abundance and presence, although a reasonable number (30+ inside the Halo region, 30+ outside) of cameras are required due to low mustelid detectability. Both occupancy models and camera trap indices may be useful to monitor relative changes of abundance in mustelids (and other pest species). This work will contribute towards a nationally applicable best-practice method for monitoring mustelid abundance and will better quantify and improve the ever increasing effort to control these predators.

This work was funded by Predator Free 2050, supported by funding from the Strategic Science Investment Fund, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, and Predator Free Dunedin.

CONTACT

Andrew Veale

vealea@landcareresearch.co.nz