Ghost hosts: Deer, pigs, and TB eradication

Possums are the main wildlife vector of bovine tuberculosis (TB) in New Zealand, but pigs and deer are spillover hosts of the disease. Replicated large-scale field trials show that greatly reducing possum densities but not deer or pig densities results in the prevalence of TB in deer and pigs falling towards zero, albeit slowly in deer.

Graham Nugent and his colleagues believe this is strong evidence that neither species can independently sustain TB in the wild under New Zealand conditions, even though they can do so under more crowded conditions on farms or overseas. Their spillover status is surprising, given that in some places the prevalence of TB in adult pigs can approach 100%, and over 50% in adult deer. The good news implicit in such spillover status is that control of pigs and deer is therefore not an essential component of TB eradication, so the economic and social cost of pig and deer control can be avoided. However, both species remain important in New Zealand’s TB management programme.

Pigs become infected wherever they share habitat with infected possums because they readily eat carrion (including dead possums), often in large groups (Fig. 1), and are important for two reasons. First, they are far more wide-ranging than possums, so once infected, they have the potential to carry TB long distances, possibly to areas where there are no infected possums. For example, an uninfected radio-collared sow released in Hochstetter forest on the West Coast was killed 32 km away 15 months later, along with three of her offspring, and all four of them were infected. This is far beyond the usual pig home radius of a few kilometres. The risk is that ferrets and very occasionally possums, could scavenge on the remains of such dispersing pigs when they die or are killed, and thereby establish a new outbreak of TB. This risk is made worse by hunters transporting live or dead pigs to faraway areas and then releasing them or dumping carcass remnants in places where other wildlife can scavenge them.

Pigs become infected wherever they share habitat with infected possums because they readily eat carrion (including dead possums), often in large groups (Fig. 1), and are important for two reasons. First, they are far more wide-ranging than possums, so once infected, they have the potential to carry TB long distances, possibly to areas where there are no infected possums. For example, an uninfected radio-collared sow released in Hochstetter forest on the West Coast was killed 32 km away 15 months later, along with three of her offspring, and all four of them were infected. This is far beyond the usual pig home radius of a few kilometres. The risk is that ferrets and very occasionally possums, could scavenge on the remains of such dispersing pigs when they die or are killed, and thereby establish a new outbreak of TB. This risk is made worse by hunters transporting live or dead pigs to faraway areas and then releasing them or dumping carcass remnants in places where other wildlife can scavenge them.

Second, pigs are very good at finding and eating possum carcasses (Fig. 1), and are therefore cost-effective detectors (sentinels) of continued TB presence in areas where possum numbers have been greatly reduced to break the TB cycle. Like canaries, once used as an early warning system of invisible gas risk in coalmines, pigs are now frequently used to help show which areas have become free of TB. They are especially valuable in this role in large unfarmed areas where ‘proving’ TB absence by direct survey of low density possum populations is almost prohibitively expensive. In some contexts, surveying a single pig can be more cost-effective than setting 100 possum traps. The main drawback to using pigs as sentinels is that they are not always available. But even that problem can sometimes be overcome by releasing sentinel pigs into areas where possum surveys are impractical.

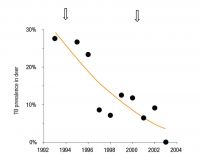

For deer, the issues are different. They interact with TB infected possums and possum carcasses far less than pigs and their usefulness as sentinels is thought to be a hundred times lower than for pigs – except where there are very few pigs, when deer surveys can sometimes be cheaper than possum surveys. Unfortunately, despite being weak sentinels, when deer become infected they can carry infection for up to 15 years. Unlike possums (which mostly die within six months of becoming infected), and much more like humans, many deer that become infected do not immediately develop full-blown tuberculosis – rather they remain latently infected until, through age or ill health, their immune system is no longer able to keep the latent infection at bay and the animal develops and dies of tuberculosis. This makes it possible for TB to be eradicated from a local possum population within as few as five years of possum control being started, but for the ghost of past infection to live on in deer for another decade after that (Fig. 2). The problem is that if possum control is stopped after 5–10 years, possum numbers can increase back to the levels at which TB can persist before the last infected deer dies. This creates a tiny but not negligible risk that TB can re-establish in such possum populations and start a new epidemic. As a consequence, possum control has to be maintained for at least a decade in areas where significant numbers of infected deer were once present.

Thus, despite not being maintenance hosts in their own right, wild deer and pigs will remain an important part of the New Zealand TB control programme for its entire duration.

This article is based largely on research funded by TBfree New Zealand and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Fig. 1 Scavengers extraordinaire – trail camera images of resident and released wild pigs feeding on possum carcasses, showing how a single tuberculous possum carcass can infect a large number of pigs.

Fig. 2 Gradual decline in TB prevalence in deer in the eastern Hauhungaroa Range in the central North Island after possum control in 1994 and 2000 (arrows).