Community group finds no increase in rat numbers as possum numbers are reduced

Competitor release is an ecological interaction in which controlling or eradicating one pest species causes another competing species to increase in number. For example, in some New Zealand forests, after possums and ship rats are controlled with widespread toxic baiting ship rat numbers climb higher than before control. This is because ship rat populations recover more quickly than possum populations and benefit from reduced competition with possums for foods such as seeds, fruit and invertebrates. When abundant, rats can prey heavily on indigenous species, potentially undoing some of the conservation benefits of possum control.

The Otago Peninsula Biodiversity Group (OPBG) has been working to eradicate possums over the Peninsula since 2011 to protect biodiversity, along with lifestyle and economic values. The Peninsula is very different from the forests where competitor release of rats has been shown: it has residential communities, steep pasture, exotic trees, and pockets of indigenous shrub and forest.

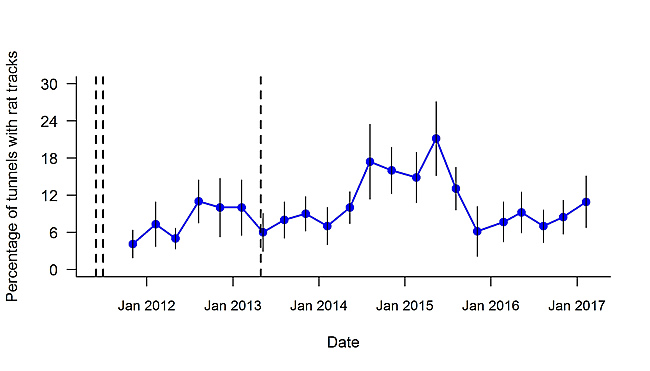

Possums, identified by the OPBG and the community as the most controllable animal pest, were the group’s first target. The OPBG removed possums with toxic bait (in bait stations) and traps, starting at the tip of the Peninsula and working towards the suburbs of Dunedin. The main possum knockdown operations were done in March to June 2011 (northeast end of Peninsula) and December to April 2013 (southwest end) (Figure 1). These operations were followed by mop-up and hot-spot possum removals that are ongoing.

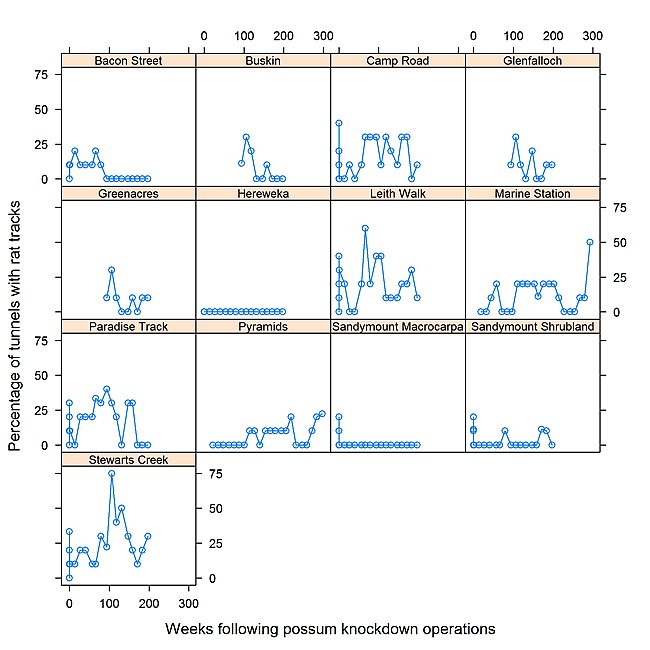

OPBG founding trustee Moira Parker was concerned that a rat population increase on the Peninsula could undermine the benefits of possum removal, particularly as ship rats are one of the most important predators of birds’ eggs and nestlings in forest fragments and urban and peri-urban environments. With Rik Wilson, Cathy Rufaut and Deb Wilson, she established a network of inked footprint-tracking tunnels to test for changes in rat numbers on the Peninsula, and these were checked on a single dry night every 3 months for 5 years. The proportion of tunnels containing rat tracks on each line of tunnels was used as an index of rat abundance – ship rats and Norway rats combined, as the two species cannot be distinguished from their tracks.

The OPBG removed 11,300 possums between 2011 and the final rodent monitoring session in February 2017. They estimated that in some parts of the Peninsula possum density reached 20 per hectare prior to control.

Peninsula rat tracking over time

The proportion of tunnels with rat tracks fluctuated annually and seasonally (Figure 1), as is typical of rat populations in New Zealand, and varied among the 13 lines of tunnels (Figure 2) due to differences in habitat, land use, and pest control by landowners. However, statistical modelling showed that the rat tracking rate was not related to the number of weeks since possum knockdowns. The group concluded there was no evidence that 5 years of possum control had caused the rat population to increase.

Why was competitor release of rats not evident on the Peninsula?

The OPBG project differs in several ways from earlier studies that showed competitor release of ship rats after possum removal. These differences may explain why findings on the Peninsula contrast with earlier research results.

First, foods competed for by possums and rats in the diverse Peninsula habitats would be very different from those in North Island forests. It may be that the diets of rats and possums on the Peninsula overlap less than in forest.

Second, Peninsula possum control operations were targeted at possums and did not kill many rats. In the earlier studies, surviving ship rats were released also from competition with rats that had been killed by aerial baiting. Perhaps only after both mammals become scarce do remaining rats have sufficient food to stimulate rapid reproduction and population growth.

Third, possum removal from the Peninsula with trapping and bait stations has been relatively gradual compared with that following aerial baiting. Progressive possum control could affect the movements and diets of both possums and rats and prevent competitor release of rats, or make it difficult to detect.

Finally, ship rats are the predominant rats in forests and shrubland, whereas Norway rats are often urban, on farms, or near water, but the OPBG did not determine which species of rats left footprints in the Peninsula tunnels. Given the Peninsula’s patches of forest and shrublands, long coastline, streams, farms and villages, both rat species may have tracked the tunnels. Differences in their ecology and behaviour could obscure the relationships between tracking rates and time since possum control.

Future monitoring on the Otago Peninsula

The tracking data provide a baseline to assess the outcomes of future Peninsula predator removals. For example, if further rat control is implemented, these data could be used to test for changes in tracking rates of rats and of other species that tracked the tunnels, including house mice (which can increase in numbers following ship rat removal), and indigenous skinks and geckos.

For other groups considering similar projects, a modified monitoring design may be better able to detect consistent long-term rodent population changes. First, focusing on one or a few habitats of interest, such as indigenous forest fragments, would reduce between-habitat differences in rodent tracking rates. Second, comparing rodent numbers on both pest removal and non-removal sites would allow site differences to be separated from the effects of pest control. Finally, using additional monitoring devices (such as chewcards) alongside tracking tunnels could help confirm whether differences in rat tracking rates are related to the presence of possums or other pest species.

Information about the OPBG can be found at www.pestfreepeninsula.org.nz. Reports on the rat-tracking study and other Otago Peninsula projects can be found at www.pestfreepeninsula.org.nz/?page_id=596

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Otago Regional Council’s Environmental Enhancement Fund awarded to the Otago Peninsula Biodiversity Group, and by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Strategic Science Investment Fund. Twenty-seven Otago Peninsula residents undertook the fieldwork, and Carol Tippet managed the data and logistics in this citizen science project.

Deb Wilson

wilsond@landcareresearch.co.nz

Moira Parker (Otago Peninsula Biodiversity Trust)

Cathy Rufaut (Otago Peninsula Biodiversity Trust and University of Otago)