Tracking climate change awareness among rural decision-makers

Over the coming decades, changes in climate are likely to have serious effects on New Zealand’s productive land environments. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects a 0.8°C increase in temperature by 2040 for New Zealand, as well as more extreme rainfall events and increased drought severity.

The results of the biennial Survey of Rural Decision Makers, run by scientists at Manaaki Whenua, show that farmers are more aware than ever of the risks of climate change on their activities.

With between 3,000 and 5,000 farmers, foresters, growers, and lifestyle block owners from Cape Reinga to Bluff taking part in each wave, the survey records current practice and future planning across the breadth of the primary sector.

Most respondents believe climate change is already affecting New Zealand, and roughly three-quarters anticipate that the frequency or intensity of drought, heat waves, flooding, and storms will increase in the future.

Encouragingly, most farmers, foresters, and growers had introduced management practices to mitigate climate change effects, such as changing stock rates, planting native trees, increasing feed reserves, changing stock breeds, investing in infrastructure to stop flooding, and increasing water storage. Of note, most farmers would rather plant indigenous trees, but feel that the poor rate of return is a barrier.

In work linked to the survey, Manaaki Whenua’s Pike Stahlmann-Brown, Pam Booth, and Patrick Walsh investigated the drivers behind this increased awareness of climate issues. Using experience of drought as an example of a climate change event, they also estimated how far back farmers draw on their experiences to plan for the future.

Not surprisingly, the team found that recent exposure to drought significantly increases expectations regarding future drought, and the greater the intensity of the drought, the more likely farmers are to think that drought will increase. Personal experience makes climate change feel more relevant and immediate, increasing the likelihood that individuals become concerned about it.

However, the researchers also showed that farmers most strongly refer to the past 5 to 10 years rather than the longer historical record when evaluating a drought’s intensity. This may create future problems, because if, for example, an area experiences a few ‘good’ years amid a prolonged drought, people are less likely to adapt to the overall change. This is an important finding for effective policy-making: policies and guidance for farmers that rely on increasing perceptions of risk to spur them to act may overestimate how much risk farmers actually perceive.

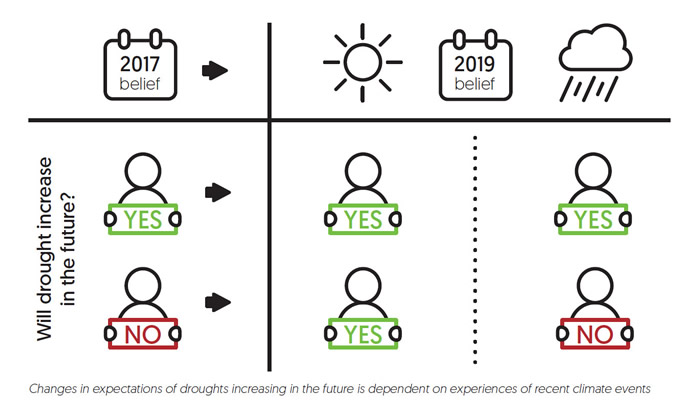

Further work in this area by Stahlmann-Brown and Walsh (in press) has found that experiencing drought causes people to change their mind about the future risk of climate change, but only among people who don’t already believe that drought will increase. Extreme weather is an impetus for people to start believing in climate change, but once people accept it, they tend to stick with their new belief.

This may be another encouraging sign: as New Zealand moves towards more frequent and more severe drought, farmers, foresters, and growers may increasingly agree with the scientific consensus, raising the likelihood of future farm-level and public action.