Kauri Dieback: Kia Toitu he Kauri

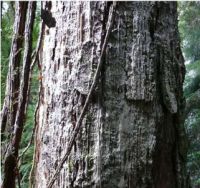

Infected kauri tree.

As well as finding plant diseases to use as methods of mass weed destruction, our plant pathologists get called on to help out when all is not well with native plants.

Unfortunately the increased movement of people and goods around the world is allowing plant pathogens to infect new hosts, often with devastating results. In New Zealand the discovery of diseased kauri (Agathis australis) in Northland in 2003 was a huge blow. Not only is this iconic, ancient species of high cultural importance to Maori, it is the dominant canopy tree species providing the framework for one of our primary forest ecosystems.

When kauri trees in the Waipoua Forest started showing symptoms of disease a decade ago Phytophthora was the prime suspect. Species of Phytophthora (which literally means “plant destroyer”) have been responsible for many serious plant diseases, including the Irish famine when potatoes became infected in the 1840s, but also more recently affecting a range of trees worldwide including oak, chestnut, alder and jarrah. Phytophthora is a soil-borne microbe (or water mould). In kauri it initially affects the roots and subsequently disrupts the function of the secondary cambium and phloem resin cells, causing lesions on the lower trunk, leaf chlorosis, canopy dieback and ultimately the death of the tree. All age and size classes, from trees that are only 3 years old to huge trees that are over 800 years old, can be affected, posing a serious threat to the last remaining natural remnants of kauri in Northland, Auckland, and the Waikato.

Diseased kauri trees had been known from Great Barrier Island for several decades. The causative agent was identified as Phytophthora heveae in 1974, but after the discovery of diseased plants on the mainland, further investigations showed this to be incorrect and the pathogen was given the provisional name of Phytophthora ‘taxon Agathis’ or PTA. It is not known how the plants on Great Barrier Island or on the mainland became infected, but the disease is likely to have been accidentally introduced. The genus Agathis (Araucariaceae) includes at least 13 species that can be found in temperate areas in the southwest Pacific including, Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia, Australia, and New Zealand.

Once the threat to kauri became apparent, a multi-agency Kauri Dieback Joint Agency Response (KDJAR) group was established including four regional councils (Auckland, Bay of Plenty, Northland and Waikato), the Department of Conservation (DOC) and the Ministry for Primary Industries. M ā ori (tangata whenua), Crown research and university scientists contribute to a technical advisory group supporting the long-term management response. Well-attended public symposia resulted in government support for research efforts to “Keep Kauri Standing”. Research funds have been used to identify the species of Phytophthora, develop diagnostic tools, determine the extent of the disease, understand key pathways for spread, determine if other plants are at risk and develop control tools and strategies. A report on this research has recently been completed by Landcare Research.

Identifying which species of Phytophthora is responsible for kauri dieback was a critical step towards understanding and managing the disease. Ross Beever initially led the work, with the project suffering a large set-back when he died in June 2010. Ross and his team used a combination of DNA based diagnostics and morphological analysis to conclude that there are five different Phytophthora species present in kauri forest soils; P. cinnamomi, P. cryptogea, P. kernoviae, P. nicotianae and PTA. Further molecular studies confirmed that PTA was a new species to science, most closely related to another new species of Phytophthora, previously considered to be P. castaneae. PTA will soon be formally named Phytopthora agathadicida (kauri killer), although its geographic origins remain uncertain.

Pathogenicity studies conducted by Ross Beever suggested that only kauri is killed by P. agathadicida. Kauri seedlings inoculated with the disease showed signs of stress after 3 weeks and were dead after 7 weeks.

Diagnostic methods to test for the presence of P. agathadicida have been investigated. Overseas stream-based sampling is often used to detect Phytophthora. Simon Randall, Masters student at the University of Auckland, trialled this technique in the Waitakere Ranges to test its effectiveness as a passive monitoring method. Simon placed leaves from five different tree species in streams running through the kauri forest for 3 weeks and then retrieved them to see if they had been inoculated with Phytophthora. The results showed that the method was useful for detecting Phytophthora spp. (e.g. P. gonapodyidies, Phytophthora ‘taxon Pg chlamydo’, P. kernoviae, and P. multivora) and sensitive enough to pick up differences between sub-catchments. The technique demonstrated that it could detect soilborne Phytophthora species (e.g. P. multivora) but P. agathadicida was not detected, despite being present in the area. Phytophthora species can only sporulate in free water, and it was determined that P. agathadicida could be detected by flooding soil samples and then catching the motile zoospores on leaf baits. However, both stream- and soil-based detection take a significant amount of time (10–20 days) to complete and require specialist training to recognise Phytophthora from other pathogens. Modern nucleic acid detection techniques (e.g. TaqMan real-time PCR chemistry) are now being developed that will in time allow the presence/absence of P. agathadicida to be rapidly and decisively determined.

Between 2011 and 2013, two rounds of soil-based surveillance were funded by the KDJAR. Landcare Research managed this work and utilised Phytophthora expertise at Scion (Drs Nari Williams, Peter Scott, Rebecca MacDougall) and Plant & Food Research (Dr Ian Horner, Ellena Hough). Phytophthora agathadicida has now been confirmed from a number of forests in the Northland region (Trounson Kauri Park, Omahuta, Glenbervie, Mangawhai, Kaiwaka, Raetea, as well as Waipoua) and forest remnants in the Auckland Region (Waitakere Ranges, Awhitu Peninsula south of Manukau Harbour, North Shore/Albany, Waimauku/Muriwai) as well as Great Barrier Island. Stands further south (i.e. Coromandel Peninsula) currently appear to be free of the disease.

Between 2011 and 2013, two rounds of soil-based surveillance were funded by the KDJAR. Landcare Research managed this work and utilised Phytophthora expertise at Scion (Drs Nari Williams, Peter Scott, Rebecca MacDougall) and Plant & Food Research (Dr Ian Horner, Ellena Hough). Phytophthora agathadicida has now been confirmed from a number of forests in the Northland region (Trounson Kauri Park, Omahuta, Glenbervie, Mangawhai, Kaiwaka, Raetea, as well as Waipoua) and forest remnants in the Auckland Region (Waitakere Ranges, Awhitu Peninsula south of Manukau Harbour, North Shore/Albany, Waimauku/Muriwai) as well as Great Barrier Island. Stands further south (i.e. Coromandel Peninsula) currently appear to be free of the disease.

Working out how to prevent the disease from spreading further has been another important area of research. “The primary vector for kauri dieback appears to be movement of soil between forests on footwear, bikes and equipment,” said Stan Bellgard, who took over the project following Ross’s death. Soil collected from boot-wash stations contained three Phytophthora species, demonstrating the need for phytosanitary measures to contain the disease. “We were surprised to find that the Phytophthora remained viable within the soil for at least a year. Chemicals such as Trigene Advance II are effective against the mycelium of Phytophthora, so we are encouraging the public to clean their boots and bikes with a 2% solution,” added Stan. To try to prevent further spread of the disease, an extensive public awareness campaign has been launched in the Auckland and Northland regions. Signage and foot-wash stations have been established at the start and finish of popular walking trails. DOC has invested significant resources into building boardwalks around some of the most famous and best loved kauri trees, such as Tane Mahuta, which attract a continuous stream of tourists. Community-led efforts to inform hunters, mountain bikers and trampers about the importance of cleaning footwear to prevent soil transfer between forests have been initiated but the gravity of the situation does seem to be lost on some forest visitors. A recent survey of people using the kauri forests for recreation conducted by Auckland Council found that despite numerous public meetings and media messages, engagement with the public was poor and that compliance rates were below 40%. Better public support is needed to prevent further spread of the disease.

There still remains a lot to do. Lines of kauri will be screened by Scion in Rotorua from throughout its natural range to look for any natural resistance to the disease. If resistant lines can be found they will be bred up as replacement plants for devastated areas. Plant & Food scientists are also looking at whether resistance can be boosted by injecting kauri with phosphite. “This technique gave excellent control of P. agathadicida in glasshouse trials with potted kauri plants,” said Ian Horner. “Early results from trials with infected trees in Auckland and Northland forests are also looking very encouraging,” he said. Further research is also needed to better understand the risk kauri dieback poses to other native New Zealand plants. Some infection has been achieved under laboratory conditions that may not occur in the field. With the initial research results now available it is hoped that further funding can be secured to allow this important research to continue and kauri to remain giants of the New Zealand forest.

Funding for this research was provided by the Ministry for Primary Industries and the KDJAR.