Catchment stabilisation to protect coral reefs in the Pacific

A new community-based model to better protect coral reefs around pacific islands through better land management could easily be adapted to Aotearoa’s coastline, researchers say.

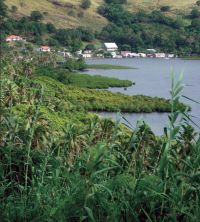

Sedimentation of near-shore coral is a visible impact for Pacific Island communities who rely on coral reefs for fishing, tourism and maintaining traditional cultural values.

Landcare Research scientists Andrew Fenemor, Colin Meurk and Grant Hunter led the compilation of a Best Practice Guide for community action and revegetation in Pacific Island hill lands, to support community initiatives to protect coastal resources. The guide was developed for the French-funded Coral Reef InitiativeS for the Pacific (CRISP) and co-authored with experts from the University of the South Pacific (USP), Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), Vanuatu Farm Support Association (FSA) and Fiji Department of Forestry.

The Pacific project empowered communities to undertake sustainable management decisions in the protection and restoration of their catchment areas. It applied an Integrated Catchment Management (ICM) “ridge to reef” approach highlighting the connectivity of land-use practices in the upper catchment and their impacts in the marine environment. The guide particularly draws on USP and FSA work with communities in the Naroko and Nakorotubu catchments of north-east Viti Levu (Fiji) and Epau and Aneityum in Vanuatu, but the principles apply to any Pacific hill lands.

And Mr Fenemor says because Māori and Islanders in the Pacific have some similar cultural traditions for managing natural resources, the same principles could easily be applied in Aotearoa.

“Marine resources such as kaimoana are susceptible to catchment runoff of sediment and contaminants, so knowledge about how to manage these catchment areas is vital. Catchment management is also made easier if communities have responsibility for the coastal resources adjacent to their villages and catchments upstream, as was the case in the two Fiji case studies in this project – and active management across those two domains is an aspiration for many iwi in New Zealand as well.”

The guide offers a step-wise process for agencies and local communities to manage their sediment loss:

- Engaging communities and raising awareness

- Identifying problems and vision as part of a planning process

- Identifying erosion risk according to simple, easily applied field criteria, recognising where in the landscape these risk classes occur (based on land units on maps and oblique aerial photographs), and ecologically characterising these land units

- Providing a palette of (safe) species suitable for each named land unit, and providing choices among these palettes according to use value (timber, building, crafts, fi bre, medicine, pasture, crop/food, and biodiversity) and propagation process

- Applying planting and maintenance techniques that ensure best results for effort and resources, and

- Carrying out a monitoring regime and learning from the process through an adaptive management cycle.

“I think the ICM management process, the tools for identifying areas of greatest risk of sediment loss, and the revegetation methods identified in the Pacific Islands guide could also be a useful source of information for Māori seeking to resolve similar problems at home,” Mr Fenemor says.

“The simple community-led erosion risk characterisation needs some refinement and testing, so we (the authors) would be happy to hear from anyone wanting to try it out.”