Manaaki Whenua science supports the re-establishment of a customary harvest of kuia (grey-faced petrels) by Ngati Awa, Bay of Plenty

Kev Drew marking out burrow survey plots

Manaaki Whenua scientists are offering new insights into the re-establishment of a traditional seabird harvest by Ngāti Awa from Moutohorā (Whale Island) that has been subject to a rāhui (self-imposed ban) since the late 1950s because of concerns over declining population numbers.

Although the exact cause of the decline in kuia (grey-faced petrel) isn’t known, the introductions of rats and rabbits to the island are believed to have had significant impacts, to the extent that few chicks fledged at all between 1972 and 1977.

Both pests were eradicated from Moutohorā by 1987, which resulted in increases in the birds’ breeding success rates, but the rāhui has remained in place until now because of uncertainties about what constitutes a “safe” level of harvest.

However, researchers from Manaaki Whenua, in collaboration with Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Awa, are studying kuia to determine adult survival and breeding rates and what an annual customary harvest of pre-fledging chicks would mean for the population co-managed by a joint management committee (Te Tapatoru a Toi) and the Department of Conservation (DOC).

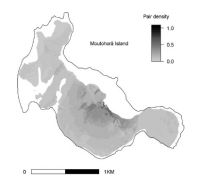

Researcher Phil Lyver says that one of the initial goals of the research was to estimate the current size of the kuia breeding population on Moutohorā. To do this, researchers measured breeding burrow density and carried out occupancy surveys, which coincided with the peak laying period and late chick-rearing periods, over three breeding seasons. These data, together with a range of environmental data, including information about soil, topography and vegetation, were analysed to estimate breeding pair density and breeding success, and to calculate the total number of breeding pairs for the island.

It was estimated that Moutohorā had about 0.02 burrows per square metre, of which around 55% were occupied by breeding kuia. Approximately 48% of the eggs resulted in chicks. Soil type, altitude, topography, canopy and ground cover were important for predicting burrow density. When incorporated into a predictive habitat model, these data translated into a population estimate of approximately 84,000 breeding pairs on the island (Figure 1).

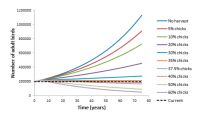

Using this information, the second goal of the study was to determine what would be a safe customary harvest, and to compare the relative effects of a range of harvest rates and strategies. To estimate these, a mathematical population modelling approach was used to assess the relative effects of removing from 5 to 60% of pre-fledging chicks each year from the island.

Researcher Chris Jones says without harvest the kuia population was estimated to grow at just over 2% per year, which is within the range of published estimates for long-lived, slow-reproducing petrel species.

With harvest intensities of up to 30% of chicks, the modelled population continued to grow, albeit at reduced rates (Figure 2).

The study reports that, in general, harvesting a fixed proportion of chicks is ‘safer’ for sustaining the harvested population than a fixed quota strategy based on taking some set number of chicks each year. This is because with a fixed- proportion harvest strategy, if the population declines for some other reason, the number of animals harvested declines proportionately.

However, in practical terms, a fixed-quota harvest is easier to manage because it is easier to count the number of chicks harvested than to estimate the total population size every year (which would be required to guide a fixed-proportion harvest).

There are therefore two general options for managing harvest of kuia chicks on Moutohorā:

- Set a very conservative fixed-quota harvest limit that would be sustainable under most circumstances outside of some unpredictable catastrophic impact on the breeding population.

- Develop a robust index of population size (such as a harvester “strike rate”) and use this to detect changes in the breeding population over time. This would then allow a fixed-proportion harvest strategy to be used.

Fig 1. The predicted density distribution of breeding pairs of kuia on Moutohorā (Whale Island). Darker colours indicate areas of higher predicted pair density, with density values per square metre. White areas represent regions of the island where density predictions were not made due to unsuitable habitat (i.e. steep cliffs, or rocky or sandy substrate).

Fig 2. The relative effects on the number of breeding adult kuia of removing a range of fixed percentages of pre-fledging chicks per year over 80 years from Moutohorā. The black dashed line indicates the current estimated number of adult birds in the population.