Can rabbit control reduce feral cat numbers at a regional scale?

Feral cat. Image - Patrick Garvey.

One of the most important factors affecting the abundance of predators is the availability of their prey. In New Zealand, introduced rabbits support populations of introduced predators, including feral cats. The abundance of rabbits may therefore affect the level of predation by cats on native birds, lizards and invertebrates.

Previous research by Grant Norbury and colleagues suggested populations of predators can be controlled by reducing the abundance of their introduced prey. However, the strength of this relationship is unclear because accurately measuring the numbers of rabbits and cats is expensive and time-consuming. Mark–recapture and/or radio-telemetry studies have been used, but such methods are too expensive to be applied routinely or at regional scales. An alternative is to use a relatively inexpensive measure such as spotlight counts to produce indices of pest abundance. However, these counts are imprecise, and predictions based on them may be unreliable.

Al Glen and colleagues took advantage of a new modelling approach that allows the abundance of rabbits and cats to be estimated explicitly from spotlight counts. Stafffrom Otago and inland south Canterbury (Mackenzie Basin) regional councils conducted spotlight counts of rabbits and cats along 66 transects between 1990 and 1995 (Fig. 1). Spotlighting was conducted on two (usually consecutive) nights for at least two sessions per year on each transect. The data were allocated to summer (September–February) and winter (March–August), corresponding approximately to the breeding and non-breeding seasons for cats. Repeated sampling within these seasons allowed detection probabilities to be estimated for both species. With this information, spotlight counts were then used to estimate abundance of rabbits and cats each season, and these estimates were used to model the response of cats to fluctuations in rabbit numbers.

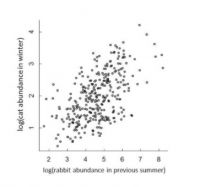

The abundance of both rabbits and cats fluctuated seasonally, being highest in winter and lowest in summer, partly due to rabbits and juvenile cats becoming more detectable by spotlighting in early winter (Fig. 2). In addition, the abundance of cats was strongly influenced by rabbit numbers in the previous season (Fig. 3). Although past work has suggested that cat populations are influenced by the abundance of rabbits, the strength and generality of this relationship was previously unknown.

These results confirm that rabbits contribute to inflated numbers of feral cats at a regional scale in the South Island. By supporting high numbers of feral cats, rabbits might indirectly intensify cat predation on native species: a process known as hyperpredation. Thus, rabbit control may not only directly reduce the damage rabbits cause to pasture and native vegetation, but may also indirectly reduce cat predation on native fauna. However, some caution is required with this approach. Sudden reductions in rabbit numbers can increase predation on native species in the short term. Faced with a shortage of rabbits, cats may simply eat more native prey. Because such prey are generally less abundant than rabbits, cat numbers will eventually decline, but not before they have eaten many native animals. To avoid this possibility, rabbits should not be controlled in isolation, but rather cats should be controlled at the same time.

So, why not simply control cats and ignore rabbits? There are two main reasons. Firstly, if rabbits are plentiful, cat numbers can recover rapidly after control, so any benefits may be short-lived. Secondly, rabbits are themselves harmful to native ecosystems and agriculture, so reducing their numbers has direct benefits in addition to helping suppress the numbers of feral cats.

Al and his colleagues are not the first to suggest that rabbit control could be used to reduce the abundance of feral cats in New Zealand. Their models confirm previous observations that cat populations are strongly influenced by rabbit abundance and show that this relationship holds across most pastoral areas of Otago and the Mackenzie Basin. By adopting a multi-species approach, in which rabbit and cat populations are targeted simultaneously, they suggest that both species can be supressed over large areas for long periods. This should have considerable benefits for pasture and for native vegetation and fauna.

This work was supported by core funding to Landcare Research from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Spotlight count data were collected by Otago and Canterbury regional councils for the Rabbit and Land Management Programme.

Al Glen, Jennyffer Cruz & Roger Pech

Fig. 1 Location of the spotlight transects in South Island dryland pastoral areas.

Fig. 2 The estimated mean abundance of feral cats (a) and rabbits (b) across the Mackenzie Basin and Otago. Following broad-scale rabbit control in 1990-91, estimates of both cats and rabbits fluctuated seasonally, with values highest during March – August (‘winter’: w) and lowest during September – February (‘summer’: s). These seasonal changes are due partly to rabbits and juvenile cats becoming detectable by spotlighting in autumn.

Fig. 3 Cat abundance over the 6 months March to August plotted against the abundance of rabbits during the previous 6 months (September to February).