Pest control across boundaries

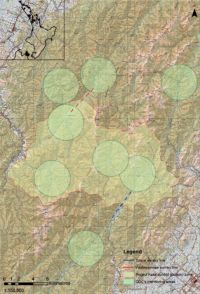

Project Kaka is large-scale (22,000 ha) ecological restoration initiative undertaken by the Department of Conservation (DOC) in Tararua Forest Park. DOC’s aim is to suppress possum, rat and stoat populations via 3-yearly aerial application of 1080 to allow the recovery of native vegetation, and invertebrate and bird communities. Control outcomes will be monitored to improve understanding of the value, safety and efficacy of large-scale pest control. The project has provided Mandy Barron and colleagues with the opportunity to test ideas about where and when to apply pest control. Mandy’s team has set up biodiversity monitoring complementary to DOC’s to test whether the area protected by pest control is larger or smaller than the area poisoned (a ‘core effect’ vs. ‘halo effect’) and whether the size of the protected area varies for different native species such as weta (an iconic invertebrate) and native vegetation.

To investigate the spatial extent and benefits of pest control, two survey lines (Totara Flats and Waitewaewae) have been set up perpendicular to the control boundary and extending 2.5 kilometres into and out of the control zone (Fig. 1). Devices to measure the relative abundance of pests (rodents, mustelids, and possums) have been set up along the lines. Resource availability (seed fall), the relative abundance of native invertebrates and tree health are also being measured to see if the benefits of pest control change with increasing distance into and out from the control zone. The duration of pest control benefits will be measured by repeated monitoring over the next 3–5 years to assess how quickly pest populations reinvade or recover to pre-control levels.

The first aerial 1080 control in Project Kaka was done in November 2010 and to date seven monitoring sessions have been completed, including one before control was applied. Not surprisingly, rats have been the species that responded most rapidly. Their tracking rates, revealed in tracking tunnels, were reduced to near-zero in the treatment zone following control but recovered to pre-control levels within 9 months (Fig. 2). By comparison, at DOC’s monitoring sites near the centre of the treatment area, rat abundance has not recovered as fast or to the same level as at our survey lines, which are both closer and more accessible to a source population from untreated parts of the Tararua Range (Fig. 1), indicative of a core effect of control on rat abundance. Possum numbers, indexed using WaxTags, have been slower to recover, although effective control across the line at Totara Flats was not achieved until August 2011. Despite this, a reduction in possum browse on kāmahi along the controlled part of this line was apparent 3 months after control, while possum browse on the entire Waitewaewae line has remained negligible. Tree weta numbers, as indicated by their occupancy of wooden shelters, have been increasing over time, averaging 34% when last checked in February 2012. There appears to be no trend in weta occupancy with respect to distance into/out of the control zone, which probably reflects the rapid recovery of rat populations across the control boundary.

To improve monitoring of the effects of predator control on native biodiversity along the survey lines, Peter Sweetapple has developed a method for indexing the abundance of native stick insects, weta and cockroaches by counting frass pellets (insect faeces) or eggs in litterfall traps. Peter has recorded variation in both measures between litterfall trap locations, with stick insect frass and eggs more common under rimu (compared with kāmahi and toro) and tree wētā frass more common in traps positioned near tree trunks compared with those under the canopy.

To investigate whether the browsing choices of possums can be explained by leaf chemistry, Hannah Windley, a PhD student at the Australian National University, has sampled foliage extensively along the monitoring lines for available nitrogen (measured in vitro; AvailN). In addition, Hannah has completed captive feeding trials to assess possum tolerance to plant secondary metabolites (anti-feedants), and how the AvailN of the foliage offered to possums influences their intake. Preliminary analysis has shown that there is a large effect of tannins on AvailN in kāmahi leaves and this resulted in possums eating more kāmahi foliage when the tannins were experimentally deactivated.

Collectively the various Project Kaka monitoring projects aim to measure the impact of pest control on both pests and native biodiversity over space and time, plus identify and explain the processes producing those impacts. The next Project Kaka control operation is scheduled for November 2013.

This project is funded by the former Ministry of Science and Innovation (contract no. C09X0909 Invasive Mammal Impacts on Biodiversity) and core funding to Landcare Research.

Mandy Barron, Wendy Ruscoe, Dean Clarke, Pen Holland, Mike Perry, Peter Sweetapple & Caroline Thomson

Fig. 1 Location of the two survey lines set up in Tararua Forest Park for Project Kaka.

Fig. 2 Indices of rat numbers with distance into the control zone in Project Kaka.