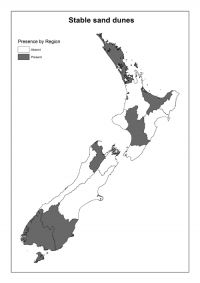

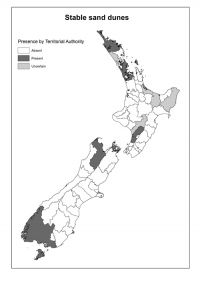

Stable sand dunes

Stabilised sand dunes with kanuka, Rangitaiki plains, Bay of Plenty (Sarah Beadel)

Stable sand dunes originate from active sand dunes comprising coastal sands. Through coastal aggradation, sand dune migration, or uplift of marine terraces (e.g., Pleistocene, early Quaternary) these dunes are now sufficiently distant from the sea to no longer be impacted by coastal disturbances. As they have become stabilised, their soils have accumulated organic matter and they are more or less completely covered in woody vegetation. In contrast to active coastal dunes, stable coastal sand dunes may support mature podocarp forest, areas of mutton-bird scrub (Brachyglottis rotundifolia var. rotundifolia), gorse (Ulex europaeus) manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) and kanuka (Kunzea ericoides var. ericoides) forest and shrubland. At many sites, the backdunes have been converted to plantation forest, mostly of radiata pine (Pinus radiata). Stable sand dunes differ from inland sand dunes in the nature of the source sands, i.e. from the sea versus from river or volcanic sand. As such, even though they occur far inland, the extensive sand dunes of the Manawatu are considered Stable sand dunes as they are derived from coastal sands.

Synonyms

Stabilised sand dunes, fixed dunes

Where do they occur?

Stabile sand dunes are found around many parts of the New Zealand coast and usually inland from current active sand dunes. They are most extensive in coastal Manawatu where the broad plain has allowed sand to migrate inland for thousands of years, with the period of maximum accumulation being about 11 000 yrs BP (Hawke & McConchie 2005). In Southland, remnants of the original podocarp forest remain, typically dominated by totara (Podocarpus totara).

Notable flora and fauna

Threatened plants include the nationally critical spiral sun orchid (Thelymitra matthewsii), nationally vulnerable Chatham Island forget-me-not (Myosotidium hortensium) and Pimelea actea. Declining species include shore spurge (Euphorbia glauca), rawiri (Kunzea ericoides var. linearis), leafless pohuehue (Muehlenbeckia ephedroides), sand daphne (Pimelea villosa), Wahlenbergia congesta subsp. congesta and New Zealand iris (Libertia peregrinans). Wahlenbergia congesta subsp. haastii is range restricted. Naturally uncommon species include bidibid (Acaena microphylla var. pauciglochidiata), Ward Beach gentian (Gentianella astonii subsp. arduana), curly sedge (Carex fretalis), Fiordland sedge (Carex pleiostachys), prostrate broom (Carmichaelia appressa), Craspedia robusta var. pedicellata, Chatham Island geranium (Geranium traversii), sand wine grass (Lachnagrostis ammobia), Chatham Island mingimingi (Leucopogon parviflorus), southern sand daphne (Pimelea lyallii) and Chatham Islands poa (Poa chathamica).

Taxonomically indeterminate species that are nationally critical include Lepidium aff. oleraceum (a) (AK 230459; Chatham Islands), Lobelia aff. angulata (AK 212143; Woodhill) and Brachyscome (a) (WELT 10278; Ward) and nationally vulnerable species include Kunzea aff. ericoides (d) (AK 255350; Thornton) and Pimelea aff. arenaria (AK 216133; Southern New Zealand), and Coriaria (a) (CHR 469745; Rimutaka) is naturally uncommon.

The katipo spider (Latrodectus katipo) is a well-known threatened sand dune invertebrate. A recent discovery in this habitat is the undescribed minute sand rove beetle (Paradiglotta sp.) Together with its sister species, P. nunni, these flightless beetles are the only members of this genus, which is unique to New Zealand.

Threat status

Endangered (Holdaway et al. 2012)Threats

Historically, extensive stable dunelands were converted into farms and plantations; very few unmodified stable sand dune ecosystems remain. Marram grass (Ammophila arenaria), tree lupin (Lupinus arboreus) and pines (Pinus spp.) have been extensively planted to prevent erosion after the native vegetation was removed. In northern areas, kikuyu grass (Pennisetum clandestinum) is a problem. Relatively drought resistant woody weeds, including gorse, barberry (Berberis glaucocarpa), boxthorn (Lycium ferossimum) and several garden escapees including climbing dock (Rumex sagittatus), all have potential to displace and/or overtop the remnant native species.

Demand for coastal property is still high so many beaches have housing on stable sand dunes; some remote areas are less affected. Development brings problems to the remaining areas in the form of intensive vehicle traffic.

Further reading

Hawke RM, McConchie JA 2005. The source, age, and stabilisation of the Koputaroa dunes, Otaki-Te Horo, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 48: 517-522.

Hesp PA 2000. Coastal sand dunes: form and function. Coastal Dune Vegetation Network Bulletin 4. Rotorua, Forest Research.

Smale MC 1994. Structure and dynamics of kanuka (Kunzea ericoides var. ericoides) heaths on sand dunes in Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Botany 32: 441-452.

Smale MC, Hall GMJ, Gardner RO 1995. Dynamics of kanuka ( Kunzea ericoides) forest on South Kaipara spit, New Zealand, and the impact of fallow deer (Dama dama). New Zealand Journal of Ecology 19: 131-141.

Smith SM, Allen RB, Daly BT 1985. Soil-vegetation relationships on a sequence of sand dunes, Tautuku Beach, Southeast Otago, New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 15: 295-312.

Wardle P 1991. Vegetation of New Zealand. Cambridge University Press. 672 p.

Wells A, Goff J 2006. Coastal dune ridge systems as chronological markers of palaeoseismic activity : a 650-yr record from southwest New Zealand. Holocene 16: 543-550.