Restoring wetlands helps Waikato River

Wetlands play a vital role in maintaining the water quality in our rivers, lakes and streams, and are considered taonga, or treasures, by Māori, but only a staggering 10 per cent remain in New Zealand. Waikato-Tainui has been working with Landcare Research to restore wetlands in the region as part of an effort to clean-up the country’s longest river.

A C+ might be considered a pass in the classroom, but when it comes to the quality of the Waikato River it doesn’t make the grade.

The mark was part of a “report card” for the catchment by the Waikato River Authority and released earlier this year. The report card considers a C and D grade as a fail.

Local iwi, Waikato-Tainui, have been working with Crown research institutes, including Landcare Research, to help restore the taonga (treasure). One approach to assist with this vision has been restoring wetlands, which play a vital role in the health of waterways.

Wetlands role:

Waikato-Tainui spokesman Rahui Papa said wetlands were important to the tribe because of their benefit to the river, which they consider an “ancestor”.

“Wetlands are the kidneys of the river. With the river so degraded after this time because of a number of different aspects, the wetlands play a wonderful role in filtering out the stuff we don’t want in the main bed of the river,” Papa said.

“Part of our work with Landcare Research will be to actually research how pristine the river was, how beneficial it was to have the wetlands in cahoots with the river and then how do we get back to that. Research is wonderful, but research that sits on a shelf and gathers dust is no good to anybody, but research that actually informs an action plan is beneficial not only to the people but to the river itself.”

Collaboration:

Through the Wetland Restoration Programme, Landcare Research and the Waikato Raupatu River Trust co-designed, co-developed, and co-implemented a variety of projects that worked towards the restoration of wetlands throughout the Waikato region.

The research partnership has run a variety of training courses to develop tribal members’ skills and expertise in wetland restoration, and monitoring of cultural indicators. Wetlands scholarships were also developed through the Waikato Institute of Technology, which saw three tribal members go through the programme and secure jobs in wetland restoration.

The partnership has also been involved with key projects such as the restoration of Maurea Islands, river islands of cultural significance to the tribe.

But it’s been a two-way street. The tribe has also had input into Landcare Research’s Wetland Restoration Programme, which is funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), providing a Mātauranga Māori perspective.

Waikato Raupatu River Trust strategy manager Nicholas Manukau said the tribe realised restoring the river requires a multi-disciplinary approach.

“The restoration and protection of the Waikato River requires collaboration amongst the tribe and Crown research institutes, the likes of Landcare Research.

“The tribe doesn’t have all the answers, but neither do the CRI’s as well, so it’s important that we collaborate and work together in partnership for the betterment of the Waikato River, its tributaries, lakes and streams.”

Cultural wetland handbook:

As part of the Wetland Restoration Programme, Landcare Research and the Waikato Raupatu River Trust have produced an online cultural wetland handbook, ‘Te Reo O Te Repo: The voice of the wetland’ to showcase iwi-led wetlands work happening around New Zealand.

Waikato-Tainui tribal member Yvonne Taura, a researcher at Landcare Research and a science research advisor at the Waikato Raupatu River Trust, said the articles in the handbook were written by Māori researchers and scientists working with iwi.

“It really is our people telling our stories from a cultural point of view,” Taura said.

“What we’re doing is showing how mātauranga Māori and science can work together to develop frameworks, initiatives, or projects that everyone can get involved in. It’s not just one telling the other, it’s together – they each have a role to play when it comes to the restoration of any ecosystem.

“We may have a different approach but we’re all aiming for the same outcome.”

She hoped the handbook would increase people’s awareness of the wetland restoration work that iwi and hapū have done around the country.

“What we really wanted to highlight were the successes and the challenges and also the great outcomes and benefits that have come from these particular projects. It was really important for our own people and the communities throughout New Zealand to really get an idea of what we’re doing in this space.”

Guidance:

Taura said the online handbook would be useful to groups around the country wanting to embark on a wetland restoration project.

The handbook aims to provide best practice techniques for the enhancement and protection of cultural wetland values to share with Māori around the country, she said.

It would also assist local authorities, research providers, and community groups in their understanding of cultural priorities for wetland restoration.

Taura believed the case studies featured in the handbook provided lessons for future restorations.

“It enables those who want to do a similar project to get an idea of what’s involved - the planning, the budget, the funding, the trials and tribulations, the successes, outcomes and benefits.”

Cultural indicators:

Landcare Research wetlands expert Dr Beverley Clarkson said the handbook was so much more than a restoration guide.

“It’s ultimately about looking after our wetlands,” Clarkson said.

“There’s been work done to show that 90 per cent of our wetlands have been destroyed since European settlement. So we have only 10 per cent left – one of the worst records in the western world, on a global scale – and the problem is that many of our wetlands that remain are steadily degrading because there’s too little water, there are too many weeds, too many pests, and too many nutrients.

“The reason we got the wetland programme going was because unless we do something about these wetlands we’re just going to lose them. We’re going to lose the tikanga, and the resources that iwi grew up with. So, it’s about helping our wetlands but also looking at it from different perspectives and trying to bring back, or restore, all aspects of wetlands. The cultural aspect is really important.”

The handbook covers how to engage with whānau, hapū and iwi, as well as tools to assess and monitor a wetland from a cultural perspective, and how to protect and enhance the cultural resources within wetlands.

“It doesn’t cover everything, but we see it as a living document,” Clarkson said.

Taura said the handbook provided examples of “taonga species” as “cultural indicators” to showcase why wetlands are so important and special to Māori.

“Taonga species are plants or animals that are important to a particular rohe, or region. A cultural indicator is a tohu, or a signal, to measure the state of a particular environment.”

Taonga species covered in the book include: flax (harakeke), watercress (wātakirhi), morepork (ruru), and whitebait (matamata).

Check it out:

‘Te Reo O Te Repo: The voice of the wetland’ is due to be launched online December 2016. The book was edited by Yvonne Taura, Cheri Van Schravendijk-Goodman, and Beverley Clarkson.

If you would like to be notified when the handbook is online, go to the Landcare Research website to register your interest.

The handbook was funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Wetland Restoration Programme.

Gallery

The online cultural wetland handbook.

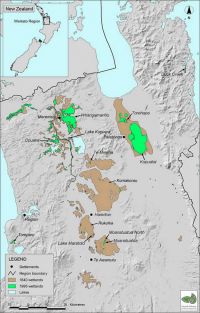

Only a fraction of New Zealand’s original wetlands remain.

The Waikato River.

Bev Clarkson and Yvonne Taura say the online handbook will help those undertaking wetland restoration.

Rahui Papa and Yvonne Taura discuss the tribe’s vision for the Waikato River.

Nicholas Manukau and Yvonne Taura admire the Waikato River.

Comments

Please note - these comments are moderated