Making pest detection black and white

Finding pests, such as wild goats, deer, pigs, and wallabies, to control numbers can be difficult at the best of times, but it is particularly difficult with small numbers across vast areas of dense shrub. However, thermal imaging technology appears a promising solution. Landcare Research has been investigating its potential in helping stop the spread of Bennett’s wallabies.

The bird’s eye view from the chopper alone isn’t enough. It’s hard to spot anything among the shades of grey vegetation and tall tussock.

But now, with the addition of thermal imagery cameras, the contrast between pests and their surroundings is black and white.

Landcare Research scientist Bruce Warburton is exploring the potential of thermal imaging cameras in detecting pests – particularly Bennett’s wallabies – to help contain their spread. The marsupials are considered a pest as they compete with livestock for pasture and damage native vegetation.

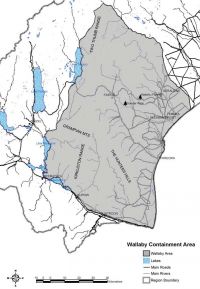

In the South Island the majority of Bennett’s wallabies remain inside a “containment area” - that is bordered to the south by the Waitaki River, to the west by the Two Thumb Range and to the north by the Rangitata River. However, since 2008 some wallabies have been seen and are known to have established south of the Waitaki River, which is a growing concern to the Otago Regional Council.

A report for the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) by Warburton and his colleagues Dave Latham and Celia Arienti-Latham into the spread of Bennett’s wallabies further south found the pest was spreading both naturally and by deliberate release, and in 50 years’ time if their current spread is not curtailed they could occupy a third of the South Island.

Environment Canterbury (ECan) and the Otago Regional Council have been working with Landcare Research to try and halt their spread.

Pilot trial:

A pilot trial around the Waitaki River, funded by Landcare Research, ECan and the Otago Regional Council, has shown the helicopter and thermal imaging camera combination looks promising.

The footage from the hi-quality thermal imaging cameras, which cost in excess of $100,000, was compared with conventional high-resolution cameras. And the difference is dramatic.

The wallabies flash up white on the screen compared to their dark background. Even when they try to hide in the thick scrub – undeterred by the helicopter hovering 60m–90m above ground - they’re visible.

The thermal technology is so sensitive it even picks up warm cow droppings.

Benefits:

Warburton said the approach has the potential to be a fast and effective way to survey an extensive area.

“Outside the containment area where there’s low numbers that’s where they’re most difficult to control because you don’t know where they are. You can spend a lot of time trying to detect them.

“With this approach we can survey a large area in a short time and potentially locate a higher proportion of animals in a given area. The next step is to compare the cost effectiveness of this approach with other methods, such as searching with dogs.”

Current methods to detect wallabies were all ground based. These included ground searches with or without detector dogs, the use of detection devices (cameras), trapping or spotlight counting.

“Everything is done on the ground, and that’s very expensive and time consuming and restrictive in the amount of area you can cover in a day.”

Warburton believed an aerial approach would be more cost-effective and efficient. Helicopters were chosen over planes as they could hover and fly lower.

Warburton said the method could also help detect and control other large species.

“We’re looking at opportunities to use it for monitoring larger species such as deer, pigs, goats, Himalayan tahr and chamois.”

Constraints:

Weather plays a key part in the success of the thermal imaging cameras detection rate.

Warburton said warm, sunny days were not good for searching as they minimised the contrast between the animal and backdrop.

Wallabies’ cool body temperature of about 12–13 degrees Celsius also made detection challenging, Warburton said. By comparison, a deer’s body temperature averages around 18–19 degrees Celsius.

“You really want a cold background, that’s why we try and do it first thing in the morning when the background is as cold as it’s going to get.

“We have to understand and work within the operational constraints of the technology.”

In ideal conditions, a 20–30 minute flight located up to 50–60 animals, he said.

Feedback:

Environment Canterbury biosecurity team leader Brent Glentworth said the pilot trial showed the new approach had “huge advantages” to help find those low numbers of wallabies in difficult high tussock country.

“That population on the south bank of the Waitaki, they’re spread over 72,000 hectares. That’s a lot of dirt for guys to cover on foot with a pack of dogs.

“The thermal imaging will potentially find those individual animals – needle in a haystack material – and let us destroy them straight away without having to spend weeks and weeks, and days and days, with shooters and dogs trying to flush these animals with the likelihood of trying to get a shot at them.”

A group of Waitaki farmers were so enthusiastic about the results they formed a group to continue testing the approach with Landcare Research.

Waitaki Wallaby Liaison Group spokesman Mike Paterson, a Kurow sheep farmer, said the new approach “looked like a very good tool” to help make wallabies “stand out”.

“If you’re looking at a hillside unless they’re jumping around and moving you can’t really spot them. Whereas, this will just guarantee that you’re not missing them and you know that they’re there.”

He believed it would improve efficiency tenfold, and could reduce the use of poisons.

“It just creates the efficiency in a chopper. It would double it by 10 times, if not a 100.“Having another tool like this can certainly reduce the reliance on 1080 and potentially be a lot more efficient and a better way of controlling them, easier on the landscape really.”

Next step:

The group is working with Landcare Research and has put in a bid to the Ministry of Primary Industries’ Sustainable Farming Fund (SFF) to try secure more funding to run full-scale trials to measure the effectiveness of thermal imagery cameras in detecting wallabies compared to conventional methods.

The project would also consider what detection and control methods were best to combine to help control wallaby numbers.

Warburton said: “If the camera detects a wallaby what do we do next? Do we have a shooter on board, or GPS them and come back a day later and look for them?”

He said shooting was often the preferred control method as there were issues using poison on farmland and logistical problems on conservation land in the area.

“They can be controlled very cost effectively with 1080 poison, but because they inhabit mostly farmland, farmers are very reluctant to seek and pay for off-site grazing for their stock, and if there is little rainfall to de-toxify the baits that might mean many months.”

If the SFF bid is successful, the project will begin mid-next year.

Background:

Landcare Research has been investigating the potential of thermal imagery cameras for some time. Its earlier research, funded by OSPRI, looked at their ability to detect possums.

“Possums are really hard to detect because you have to fly at night and they’re really small. Other species you can search for really easily in the morning when it’s light but the background temperature is at its coolest,” Warburton said.

The technology has come a long way from when Landcare Research first started investigating its potential nearly 20 years ago, he said. Back then, it could only recognise “hot spots”, not differentiate exact species. Advances in pixel resolution and frame rate meant image quality was better and also allowed the helicopter to travel faster.

Community effort:

The public’s help is needed in the war on wallabies. If you have seen a wallaby outside the containment area report it to ECan. They have some handy hints of signs to look out for.

Gallery

Low numbers of wallabies are difficult to spot against the dense, grey terrain.

Thermal imagery technology helps make wallaby spotting black and white.

Wallabies compete with livestock for pasture and damage native vegetation.

Waimate is known as ‘wallaby country’ but they’re spreading further south.

Wallabies have breached the Waitaki River.

The approach looks promising to help track low numbers of wallabies.

Kurow sheep farmers Ken and Mike Paterson are optimistic about the approach.

The containment area.

The expected spread of Bennett’s wallabies, if left unchecked.

You may also like

Comments

Please note - these comments are moderated