Fowl B.O. helps fool predators

The majority of New Zealand’s most deadly predators – stoats, ferrets, feral cats, and rats - rely on smell to hunt. But, could this be used against them? Landcare Research, in collaboration with the University of Sydney, is testing this theory to help native birds when they’re at their most vulnerable. Preliminary results look encouraging.

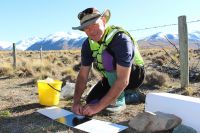

Dr Grant Norbury picks up a rock and sniffs it like inspecting a fine wine.

The stone is one of thousands the Landcare Research scientist and his team have smeared with Vaseline infused with bird odour across the Mackenzie Basin over the last 3 months in an attempt to help threatened birds, like banded dotterels and wrybills, during the breeding season by tricking predators to not always trust their nose.

The concept is called “chemical camouflage”, and it’s never been done on this scale before.

“It’s a concept of trying to mess with predators’ minds basically,” Norbury said.

“When predators are hunting, food isn’t all that abundant out here – they’ve got to be pretty efficient in the way they hunt – so they cue into signals that actually represent food. If they don’t represent food then they tend to put those cues into their sensory background. So the idea is to provide signals to them that don’t have rewards.”

Landcare Research has been testing the concept to try to boost the hatching success of banded dotterels. If the concept works it could help other braided river birds in dire straits, like the critically endangered black stilt, with a dismal population of around 100.

Proof of concept:

The concept was developed by Australian scientists, Dr Catherine Price and Professor Peter Banks, who have already conducted preliminary tests with good results.

Price successfully protected quail eggs in fake nests in Sydney bushland from wild rats by peppering the area with bird faeces and feathers for a week before the eggs went out. She found rats lost interest in the odour after only 3 days as there was no food reward. Once habituated to the odour, rats were not interested in searching for nests even when they held eggs.

As a result, the trial found a 62 per cent increase in the survival rate of nests over a short period.

“I think everyone was astounded it actually worked as convincingly as it seemed to,” Price said.

Norbury and his colleagues have adapted the approach and are using natural odour from chicken, quail, and black-backed gull to try to camouflage the banded dotterels.

Promising pen trials:

Results from extensive lab and pen trials appear promising.

Landcare Research field technician Sam Brown said lab trials with mice, and pen trials with ferrets and hedgehogs, found they “habituated”, or lost interest, in the unrewarding odours.

Importantly, most also appeared to “generalise” between odour types.

“If they became habituated to odour from one bird species, most remained uninterested in odours from other bird species, meaning that easily-available odour like chicken might induce lack of interest in odours from birds in general, including species we want to hide from predators,” she said.

Landscape-scale trial:

Norbury and his team have been manually dispersing the chicken, quail, and gull odours across approximately 1800 hectares in the Mackenzie Basin to test the concept on a landscape-scale.

Norbury said it was the first time the theory had been tested on such a large scale. By comparison, the Australian study was carried out on one-hectare grids.

“How we apply this stuff on a landscape scale will be something we need to take further if we have success with this project. With this open country I’d like to use drones ultimately. How we do it in a forest system would have its own challenges,” he said.

Every 3 days, the scent was applied to around 700 randomised GPS located points across an 800-hectare and a 1000-hectare site. Two additional non-treatment sites were also being monitored.

Eighty motion-triggered cameras were used to monitor predator interactions with the bird scent on the treatment sites, and another group of cameras and tracking tunnels was used on the non-treatment sites to monitor predator abundance.

Bird watching:

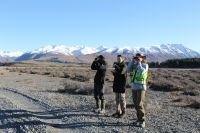

Ornithologists were also brought in to monitor how many nests successfully hatched.

Wildlife Management International Limited (WMIL) ornithologist Nikki McArthur, with the help of four colleagues, monitored around 240 nests across the four sites to observe their hatching success. Cameras were also used to see which predators were responsible for failed nests – two thirds of which were hedgehogs.

From the onset of the project, McArthur was optimistic about the idea.

“I think this is a very clever idea and it’s based on some solid theory and logic so I’m quite hopeful we’ll be able to show a difference in nesting success between the treatment and non-treatment sites, but I guess we’ll see,” he said.

“We need clever new techniques like this to solve the problems our shorebirds are facing, as most of them are still in decline. At the moment we can’t do enough pest control to reverse those declines.”

He said native birds had adapted to cope with visual predators that hunt largely by vision, such as falcon and morepork, but these adaptations were inadequate against introduced mammalian predators that hunt mostly by smell.

Extracting bird odours:

Creating the odour lures was a challenge in itself.

However, Landcare Research lab technician Matt Campion came up with a “simple solvent extraction” method to strip the odour from the chicken, quail and gull.

This involved placing bird carcasses in a solvent-proof container, then a machine that shakes it for about an hour, and then evaporating off the solvent to concentrate the odour extract. The concentrate was then mixed with Vaseline to aid the longevity of the smell.

For the next phase of the project, Campion hopes to develop a synthetic bird odour.

“The longer-term aim of the project is to identify the components in the odour that the predators, or animals, are responding to.

“If we can identify if there is half a dozen compounds of interest and we can put these together in the right proportions that’d be the route to go down.”

Preliminary field findings:

Norbury said while some predators were attracted to the scent, others walked straight past them.

“The interactions aren’t super abundant, but nor would you expect them to be because we know that only a minority of predators – what we call rogue animals – cause most of the damage to birds. So, you wouldn’t expect every single predator to show an interest, but we are certainly getting some animals very interested.

“The only down side at the moment is we’re getting interest mostly on night one of deploying the odour. We don’t get as much interest on nights two and three, which means that the longevity of the odour is limited. We’d like it to be a bit longer, but at least we’re getting those good interactions at quite a good rate on night one.”

Exciting results:

The ultimate measure of success will be the survival of the birds, their eggs, and their chicks, Norbury said.

“We measure egg survival because that’s the easiest thing to measure, and so far we’re getting quite encouraging results. We’re finding significantly higher nesting success on the treatment sites. That’s exceeded our expectations,” he said.

“To really confirm it, next year we want to swap the treatment site and non-treated site. There’s usually a lot of natural variation in nesting success between sites anyway and we only have two replicates. If we reverse the treatments and get the same results that would be very compelling.”

The 2-year project was funded close to $1 million under the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Smart Ideas grant.

Gallery

Just one of the hundreds of animal selfies captured.

A banded dotterel nest. Photo: Ed Bennett.

Matt Campion uses solvent to extract odour from a gull.

The project took place across hundreds of hectares in the Mackenzie Basin.

Sam Brown downloads footage from a camera-trap near the Cass River.

Dr Grant Norbury sets a tracking tunnel to monitor predator abundance.

Grant Norbury and Matt Campion review camera footage.

Dr Catherine Price applies bird odour to a rock.

A banded dotterel. Photo: Ed Bennett.

Feral cat prints in a tracking tunnel.

The bird odour was infused with Vaseline to help prolong the scent.

Ed Bennett, Nikki McArthur, and Dr Grant Norbury bird watching.

You may also like

Comments

Please note - these comments are moderated