Bennett’s wallabies: do they provide any lessons for eradicating invasives?

Image - Grant Morriss.

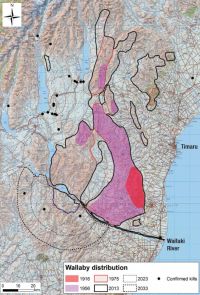

Bennett’s wallabies were introduced from Tasmania into the Hunters Hills near Waimate in 1874 to provide animals for recreational hunting. Although early records are unclear, recent DNA analysis suggests that 3–5 pairs of animals were released. Whatever the number, the species established and increased, both in distribution and numbers over the next 4–5 decades. The estimated distribution of wallabies since establishment shows that they spread at a rate of about 46 km2 per year between 1916 and 1975 (Fig. 1).

By the 1950s, the impact of wallabies on farm production was such that farmers were calling for Government intervention to control them. Since then, there have been various agencies involved, beginning with the Department of Internal Affairs, then the New Zealand Forest Service, and later still wallaby boards (similar to the rabbit boards). When the Biosecurity Act 1993 came into force, managing vertebrate pests in Canterbury became Environment Canterbury’s (ECan) responsibility. Their Regional Pest Management Strategy included wallabies. Environment Canterbury’s latest strategy has two requirements pertaining to this pest:

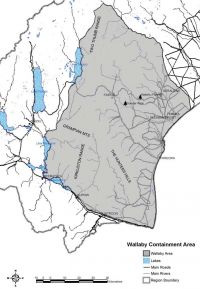

- Landowners have to ensure wallaby densities do not exceed Level 3 on the Guilford Scale (a subjective method for scoring the abundance of wallabies) on land within the Wallaby Containment Area (Fig. 2).

- Land occupiers must notify ECan within 10 working days of becoming aware of wallabies on any of their land outside the containment area, to prevent wallabies establishing there.

The first requirement (i.e. to ensure wallaby densities are kept at low levels) is standard pest control practice, and generally requires either the application of poisons (either 1080 or more recently Feratox® cyanide pellets) or shooting. However, ensuring requirement two is met is considerably harder because, at the edge of the species’ distribution, wallaby numbers are low so often difficult to detect, and the cost of their removal is high.

A recent update of the distribution of Bennett’s wallabies (Fig. 1) shows that this species has ‘escaped’ from the containment area into several new sites. One area of special concern is the south bank of the Waitaki River. Given the availability of suitable habitat for wallabies in this area and their rate of dispersal, it is likely that (without control) a further 740 km2 of farmland could be occupied by 2023, and 1480 km2 by 2033 (Fig. 1).

To successfully eradicate the wallabies south of the Waitaki River, four requirements must be met:

- Further dispersal from north of the Waitaki River must be stopped.

- The current distribution of wallabies south of the river must be known.

- All animals within this area must be able to be put at risk from either poisoning or shooting.

- It must be possible to objectively determine if eradication has been achieved.

Although this will be challenging for ECan, it will provide an opportunity to learn how best to meet the four requirements.

The lessons learnt will be applicable to eradication of other pest species with restricted distributions. The lessons from this case study will also be useful to test the technological and social challenges posed by the aspirational goal of a predator-free New Zealand.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Bruce Warburton & M. Cecilia Latham

Brent Glentworth (Environment Canterbury)

Fig. 1 Historical and current distribution and recent confi rmed kills of Bennett’s wallabies. Predicted limits of the distribution of wallabies south of the Waitaki River in 2023 and 2033 are shown by the dotted lines.

Fig. 2 Bennett’s wallaby containment area in South Canterbury (from Environment Canterbury's Pest Management Strategy, 2011).