Development of lures for stoats

Stoat. Image - Grant Morriss.

Humans are a visual species and our eyes relay the majority of sensory information we receive about the world. This reliance on sight is typical for diurnal mammals, yet many animals live in complex habitats, are active at night or forage underground – all situations where vision is naturally impaired. For these species smell is often the most important and reliable source of information. All animals continually emit odour as they move through their environment, creating a vast network of invisible chemical cues. Interception of these odours by co-existing species leads to predictable changes in behaviour, and creates an opportunity for pest managers to exploit these responses to achieve conservation goals.

The goal of ‘Predator Free New Zealand by 2050’ has given greater urgency to the search for new tools and techniques for managing invasive species. Stoats are one of three species targeted as priority pests due to the devastating toll they inflict on native wildlife. In common with other mustelids, stoats rely heavily on using odour for communication, which makes them an ideal target for olfactory lures. Predator management in New Zealand currently relies on food-based lures (e.g. rabbit meat) to attract stoats to traps or to monitoring devices such as tracking tunnels or cameras. However, food lures have limitations when deployed for managing predators. First, the effectiveness of food as an attractant is reduced when prey are plentiful. Second, after a management operation to control a pest species, the survivors become wary of food lures, while the reduction in competition increases the relative availability of prey. Third, food lures degrade quickly, reducing their appeal to any passing predator, and must be replenished frequently to remain attractive. Given the limitations of food lures it is not surprising that a concerted effort is being made to find new ‘super lures’ to improve the success of stoat monitoring and control.

This search took an unexpected turn when Patrick Garvey and his supervisors discovered that stoats are attracted to the odour of co-existing dominant predators. As part of a pen trial investigating interactions between invasive species, stoats were exposed to the body odour of ferrets and cats. The prediction was that stoats would avoid these odours because previous experiments showed they avoided the physical presence of these two competitively superior adversaries. So it was a surprise to find that stoats are strongly attracted to the odour of ferrets and cats. This response was intriguing, and its potential application for wildlife management was immediately apparent.

This search took an unexpected turn when Patrick Garvey and his supervisors discovered that stoats are attracted to the odour of co-existing dominant predators. As part of a pen trial investigating interactions between invasive species, stoats were exposed to the body odour of ferrets and cats. The prediction was that stoats would avoid these odours because previous experiments showed they avoided the physical presence of these two competitively superior adversaries. So it was a surprise to find that stoats are strongly attracted to the odour of ferrets and cats. This response was intriguing, and its potential application for wildlife management was immediately apparent.

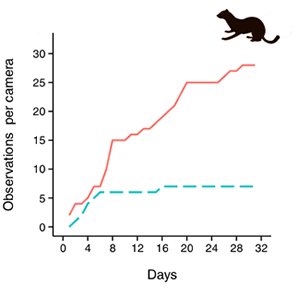

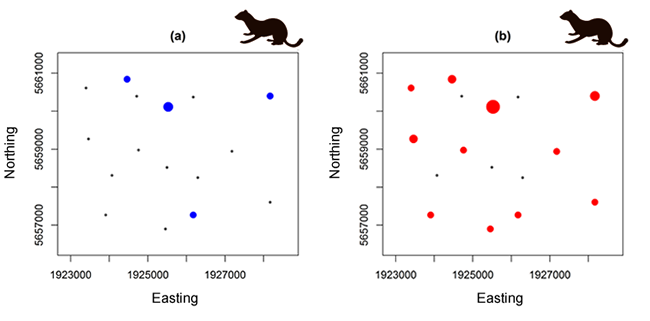

A field experiment using movement-activated cameras was devised to investigate whether ferret odour would provoke similar responses in free-ranging stoats. Over a 1-month trial, detections of stoats increased three-fold (Figure 1) when ferret odour was added to rabbit meat at monitoring sites. Estimates of site occupancy by stoats changed from rare to common with the addition of predator odour (Figure 2), whereas monitoring with a food lure alone would have considerably underestimated the distribution of stoats across the landscape. Attraction to the ferret odour was not limited to stoats, as detections of two other damaging invasive predators – hedgehogs and ship rats – also increased at the monitoring sites.

Now that a candidate lure has been discovered, the next stage is to isolate the chemicals within ferret odour that provoke this attraction. Much as a perfumer strives to create an alluring fragrance, identifying and combining the compounds that stimulate such attraction should produce a powerful lure. By creating an artificial copy of the scent rather than using the primary biological material, the life and hence effectiveness of the lure could be extended and sufficient quantities produced to provide ‘scent from a can’ for stoat control projects across New Zealand.

The development of new super lures, where attraction is provoked by hard-wired competitive and predatory behaviour, could provide a step change for the management of stoats and other invasive predators. Deploying dominant predator odour is a novel approach that could contribute to population monitoring and invasive species management in New Zealand. The research will also provide insights into the ways that animals use chemical communications. Super lures derived from predator odour should also have applications for conservation in other parts of the world; for example, in situations requiring highly sensitive detection methods for rare or endangered species.

This project is jointly funded by the New Zealand’s Biological Heritage National Science Challenge and Landcare Research.

Patrick Garvey (Landcare Research) garveyp@landcareresearch.co.nz

Bruce Warburton

Wayne Linklater – Project Leader (Victoria University)

Elaine Murphy (Lincoln University)

Craig Bunt (Lincoln University)