One-hit elimination of multiple pests and TB: does aerial 1080 baiting even come close

Camera trapping enables easy assessment of large animal abundance

In 2016 New Zealand committed to twin goals: eradicating bovine tuberculosis (TB) from possums (and other wildlife and livestock) by 2055, and eliminating three widespread predators (possums, rats and stoats) by 2050. For both goals a major hurdle will be achieving success in the vast areas of forest and steep mountain land beyond developed areas. At present the only safe, practical and affordable approach available is aerial 1080 baiting. It would therefore be useful to know how close this tool comes to achieving local elimination of the targeted pests: could such baiting be developed to deliver large-scale, one-hit elimination of multiple pest species?

Currently aerial 1080 is used to control (rather than locally eliminate) possums and/or rats as the primary targets, depending on whether the operation is TB- or conservation-focused, but it also kills some of the other pest species, including stoats. Assessments of the effectiveness of aerial 1080 have historically focused on just one or a few species, largely because different monitoring techniques are required for different species. However, the advent of trail cameras largely overcomes this problem, potentially enabling the monitoring of all terrestrial vertebrates present.

Graham Nugent, Peter Sweetapple, Grant Morriss and co-workers used a combination of chew-card monitoring, leg-hold trapping, radio-collaring, trail-camera monitoring and post-1080 carcass searches to assess the impact of an aerial 1080 operation on the abundance of large and small mammals in the Hauhungaroa Range in winter 2016. The operation was primarily targeted at achieving and confirming that the TB cycle in possums there was broken. If so, it is expected to be the last time 1080 is required there for that purpose. The operation used a moderately low sowing rate (1.5 kg of 1080 bait/ha) and most of the 80,000 ha was pre-fed twice with non-toxic bait.

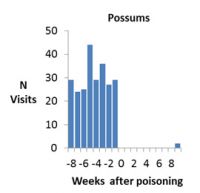

The operation killed 240 of 241 radio-collared possums – a 99.6% kill. The number of possum visits recorded at 23 trail cameras likewise declined by 99.3% (see graph). No TB was found in 332 possums necropsied for TB just before or just after the operation, and none in over 230 pigs taken from the area and checked for TB since the last known TB-infected pig was recorded in the centre of the range in early 2015.

Using mark–recapture methods, the pre-control population was estimated at about 4,000 possums, and this was reduced to about 20 after control – just one possum per 4,000 ha. At these extremely low densities, epidemiological theory indicates an infinitesimal likelihood of TB persisting after baiting, because possums usually die within 4–6 months of becoming infected and would not come into contact with other possums often enough to pass on the disease. These results leave little doubt that TB has been eradicated from possums in the Hauhungaroa Range. However, possums themselves were not eradicated.

Number of visits by possums

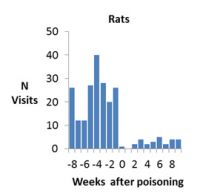

Number of visits by rats

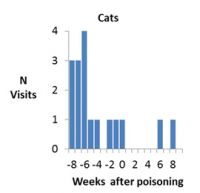

Number of visits by cats

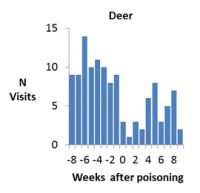

Number of visits by deer

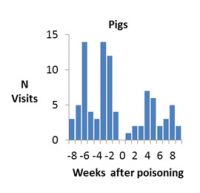

Number of visits by pigs

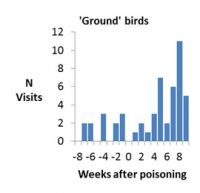

Number of visits by 'ground' birds

Number of visits by possums, rats, cats, deer, pigs and ‘ground’ birds recorded by 23 trail cameras over 8 weeks before aerial 1080 baiting and over 9 weeks after baiting. 1080 baiting occurred at the start of Week 0.

For common species other than possums, there were fewer visits recorded by trail cameras after control than before. For rats, there were no visits in the second week after baiting, but the number of visits increased soon after that to about 10% of pre-control levels (see graph). The pattern was similar for cats (and hedgehogs), but some of that increase might reflect seasonal activity patterns. Mice were recorded nine times before and eight times after 1080 baiting. Very few (four) stoat visits were recorded before control, and none in the 9 weeks after (but one has been recorded since).

The study also provided one of the first assessments of 1080 impacts across a wider suite of vertebrates than is usually monitored – red deer, goats and pigs, and common ‘ground-feeding’ birds (mostly blackbirds and thrushes). For deer, there were far fewer visits to trail cameras in the first month after poison baiting, but in the second month the visitation rate was only moderately lower (42%). The pattern was broadly similar for goats and pigs, the visitation rate for both being 46% lower in the second month after baiting compared to the month before baiting. These reductions are about the same as the annual population recruitment rate for deer and well below the recruitment rate for pigs and goats, so the medium-term impact on the density of these species will be low. In contrast to mammals, the number of visits by ground birds more than doubled.

In summary, twice-prefed aerial 1080 baiting in its current form is a highly effective tool for TB eradication, but in this study did not really come close to locally eliminating any mammal pest. Local elimination will therefore require either somehow increasing the effectiveness of 1080 baiting or finding an affordable way to locate and kill the few survivors. For the former, work is currently underway (by Landcare Research and the Zero Invasive Pest foundation) to determine whether 100% kills of possums and rats can be achieved in a single operation. For the latter, the possum example highlights the immensity of the problem: how does one find a single animal in 4,000 ha of forest? And then reliably repeat that across all such 4,000 ha areas?

The possum and TB surveys were funded by OSPRI, and the camera trapping by Landcare Research (core funding).

Graham Nugent (Landcare Research) nugentg@landcareresearch.co.nz

Peter Sweetapple

Grant Morriss

Aran Proud

Ivor Yockney