Introduction

Pegasus entrance. Image - Adrienne Farr

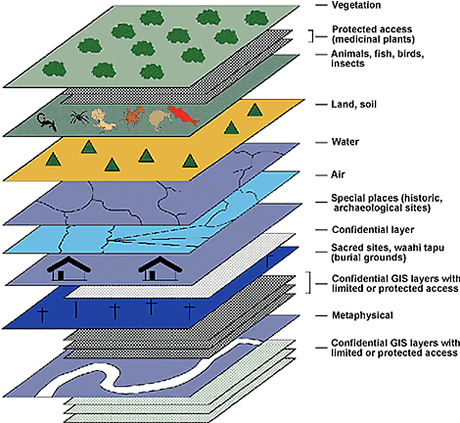

This research has involved working closely with representatives from five iwi: Ngāti Porou, Rangitāne, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Whānau-a-Apanui, and Ngai Tahu. A number of other iwi representatives have also been involved in commenting on and using the methods and frameworks developed to date and we thank them for their contribution. The main objective has been to develop methods and frameworks for recording, organising, analysing and displaying Māori values information, including mātauranga Māori (traditional knowledge), in geographic information systems (GIS) and multi-media systems. Methods are designed to take into account the sensitivity of the information, cultural and intellectual property rights, and existing Māori systems for recording this knowledge. The research is providing methods and frameworks for the development of comprehensive Māori value datasets and models specific to, and owned by, individual hapū or iwi. From these datasets information can be displayed as a series of GIS 'layers' (see Figure 1). Robust spatial infomation systems are required to assist planners to formulate planning and policy. It is hoped in future to integrate this cultural information with biophysical, economic, and social information for iwi and hapū planning.

|

|

|

In New Zealand there are legislative requirements under the Treaty of Waitangi, the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), the Historic Places Act 1993, and the Māori Land Act 1993 to include Māori cultural, historic, spiritual, and physical values in environmental / land use and social planning. These requirements are somewhat difficult to achieve at present, because the information is either sparse or lacking, difficult to obtain due to its confidential or highly sensitive nature, of variable quality across administrative areas, or often not in a form or context suitable for planning. Furthermore, the degree of consultation with tangata whenua (e.g. local iwi or hapū) required to collect this information varies from place to place, and can range from being close and constructive to non-existent. As a result, planning and policy at national, regional, district and community level as required under legislation have been difficult to achieve because of insufficient detail, substandard quality, lack of consultation, and the absence of national coordinated strategies. Present research indicates that although many regional councils and some district councils have invested much effort in this 'information needs' area, the legislative requirements remain difficult to meet.

In the preface of the Ngai Tahu resource management strategy report of the Canterbury region - 'Te Whakatau Kaupapa' (Tau et al. 1990), David Shephard, principal planning judge, wrote:

"The duty of resource managers to take into account the needs of Māori people has not been fully performed in the past. In part that has been because many planning and resource management authorities have not obtained ready and reliable sources of information about the attitudes and interests of tangata whenua. Planning decisions have been the poorer for that".

With the adoption of GIS by several iwi (as at June 1996 eight iwi in NZ were using GIS, B. Soutar, Critchlow Associates, Wellington - Suppliers of MapInfo GIS software - pers. comm.), this type of information is being increasingly stored, controlled, and accessed by individual iwi and hapū in their own premises (e.g. Ngāti Porou in Gisborne; Ihaka, pers. comm.). This obviously opens up the opportunity for local government agencies, government departments, and private companies to forge better alliances with Māori organisations, such as iwi authorities, to access Māori cultural information in future, and possibly store (under certain conditions) some of this information on their own planning databases.

The development of comprehensive information systems integrating cultural and social information with biophysical and economic information, is of paramount importance as a basis for more rational and informed debate on environmental issues, and to enable more effective land-use planning at the community and national level.