Monitoring invertebrates in community-led sanctuaries

A female Cook Strait giant wētā with BD-2 transmitter attached (Holohil Systems Ltd., Canada). Image - Danny Thornburrow.

With the rapid increase in community-led conservation projects trying to reduce mammal pests to zero or near-zero densities, there are many more opportunities to investigate how the native invertebrate fauna responds to pest control.

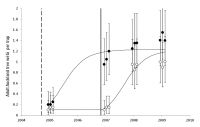

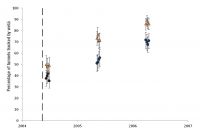

Over the past decade, Corinne Watts and colleagues have monitored invertebrates in two fenced sanctuaries – Maungatautari and Karori (Zealandia). The response of wētā populations to the eradication of mammal pests within the southern exclosure on Maungatautari Ecological Island was monitored using pitfall traps in combination with footprint tracking tunnels. Within two years of mammals being eradicated, wētā captures and the incidence of wētā footprints per tracking card dramatically increased. The mean number of adult Auckland tree wētā per trap increased 12-fold after mammal eradication and 52-fold for other wētā. This may simply reflect increases in wētā abundance following mammal eradication or it may reflect behavioural changes, or be caused by a combination of both.

Since sampling began in 1998, the ground-dwelling beetle community within Karori Sanctuary has shown no change in abundance, species richness, size distribution and trophic distribution: the beetle fauna was the same as that in the experimental control site at nearby Otari-Wilton’s Bush. However, beetle community ordination analyses (a process of grouping like species) indicate that its composition changed after most mammal species were eradicated from Karori Sanctuary. Periodic incursions of mice into the Sanctuary and the high number of ground feeding insectivorous birds (including translocated weka, tīeke, North Island robin and kiwi), may account for the lack of change in beetle densities. There appear to be species which are beetle ‘winners and losers’. These probably arise from the different feeding strategies and changes in predation pressures from introduced mammals, compared to the strategies and pressures when only mice and native birds are present.

There are now 62 community-led conservation projects on or near the New Zealand mainland, and the managers of most of them wish to introduce native birds and reptiles as soon as possible, in part to attract visitors and funding. There is also a growing demand to have iconic insect species in some of these sanctuaries. For example, Cook Strait giant wētā were translocated to Karori Sanctuary in 2007 – the first time this species has occurred on the mainland for over 100 years. These wētā were intensively monitored using radio transmitters (see photo) and were found to travel significantly further than expected (males moved up to 294 m and females up to128 m between daytime refuges over the 4-week study). The project received considerable media attention, and many people visited Karori to see the wētā. Corrine believes that within community-led sanctuaries, projects that focus on threatened invertebrates should be encouraged, as they provide easy viewing of such species for the general public and increase awareness of invertebrate conservation in New Zealand.

As more mammal-free conservation sanctuaries with pest-proof fences are established in New Zealand, understanding of how invertebrates respond to the removal of pest mammals will become clearer. Pest mammal predators may simply be replaced by native predators, especially birds (e.g. a significant decrease in invertebrate catch frequency and diversity was observed on Kapiti Island after rats were eradicated). Unfortunately, increases in the abundance and diversity of invertebrates do not always follow the eradication of mammals. Interpreting changes in the invertebrate community is difficult, complicated by both abiotic and biotic factors, and such interactions within ecosystems are poorly understood.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation through Landcare Research’s Sustaining and Restoring Biodiversity core funded research programme.

Corinne Watts, Danny Thornburrow & John Innes

Fig. 1 Changes in pitfall capture rates of Auckland tree wētā after mammal eradication in the southern exclosure (black circles) and in the adjacent forest on Maungatautari (open circles). Time of mammal eradication is shown with the dashed vertical line for the southern exclosure and the solid vertical line for the adjacent forest.

Fig. 2 Changes in tracking rates of wētā after mammal eradication in the southern exclosure on Maungatautari. Time of mammal eradication is shown with the dashed vertical line. Black circles indicate adult Auckland tree wētā and orange triangles indicate other wētā.