Can possum fur harvesters both make a living and help protect forest biodiversity?

Image - Grant Morriss.

Possums cause significant damage to biodiversity values in much of the approximately 6.5 million hectares of indigenous forest in New Zealand. Possum control programmes by the Animal Health Board and Department of Conservation (DOC) cover less than 40% of this area. In the remaining area of forest, there is little or no systematic possum control although in some localities possums are killed for their skins and/or fur. The commercial market for both of these products has survived peaks and troughs from the start of legal harvesting in 1921 through to the present day. Currently possum fur woven with merino wool forms the basis of a luxury garment industry worth around NZ$100 million per year. More than one million possums are now harvested annually to service this growing industry, but its future growth is constrained by the availability of sufficient fur.

Possum harvesting has previously been considered an unsustainable strategy to protect biodiversity values because it requires possum numbers be maintained at levels sufficient for a sustainable long-term income. In contrast, biodiversity protection (and/or bovine TB mitigation) requires much lower possum densities. Preliminary economic models, based on contemporary contractor rates and fur prices, confirm that possum fur harvest is only economically viable if possums are maintained at reasonably high densities.

In a multi-faceted project being undertaken in collaboration with the Tūhoe Tuawhenua Trust, a team of researchers led by Chris Jones has been looking at whether the apparently conflicting outcomes of an economically viable harvest and biodiversity protection can both be accommodated in native North Island podocarp forests. The researchers used interviews with local Tūhoe harvesters, trapping data, and a combination of economic and spatial population models. The interviews provided information on fur prices, local harvest strategies and trappers’ economic expectations and ‘pull-out thresholds’. The trapping data was used to estimate the effective trapping area around a harvest line and the decline in daily capture rates on the line over time. This information was then used in the models to look at the effects of two overall strategies (defined by pull-out trap-catch indices (POTCIs) of 25% and 5% (see Kararehe Kino, February 2011 for a more detailed explanation of strategies), while varying trap-line spacing and the time between successive harvests on specific lines.

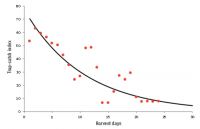

Harvesters hoped for trap-catch indices (TCIs) of 50–70% when initiating a trap-line. They stopped trapping when the POTCI was about 26% (range 20–30%), and left trapped areas for at least a year before returning. The effective trapping distance at which possums were vulnerable to capture around a trap line was 200 m. Possum captures on a line monitored over 24 harvest-days declined exponentially from an initial TCI of 63% on day 2 to under 8% from day 21 onwards (Fig.).

Simulations by the team predicted that the optimum long-term economic harvest strategy for contractors required access to sufficient habitat for 20–30 trap lines, with trapping ceasing at 25% POTCI and leaving possum populations about each trap-line to recover for three years. However, this strategy does not maintain possums at low enough densities to protect forest biodiversity. The simulations also predicted that trapping down to 5% POTCI annually with closely-spaced lines led to possum populations being held below 20% TCI over the year, which is likely to provide biodiversity gains. Furthermore, possum populations harvested during winter (which is normally the case) will be at their lowest densities during the subsequent spring and summer, when native birds and flowers of possum-preferred species are most vulnerable to predation and browse. Unfortunately, this strategy cannot provide a sustained income for a harvester, who would suffer a shortfall of $13.60 per ha of forest protected per year at the fur price of about $140 per kilogram current when the research took place

The researchers suggest that if this shortfall was subsidised by management agencies, harvest trapping could deliver the same level of possum control at lower cost than standard ground control ($45–80 per ha). The cheaper option of aerial control is still the best option for targeting possums in very rough terrain where trapping is difficult. However, to maintain pests at low densities over prolonged periods it is necessary to keep repeating the operation, and this is not economic. Aerial control does not deliver any socio-economic benefits to local communities, whereas a harvest industry could provide secure long-term employment where it is most needed and support local communities’ kaitiakitanga (traditional guardianship/duty of care) of their forest environment.

The potential therefore exists for trialling an integrated management approach, with input from the fur industry, conservation and TB disease managers, to support harvesters to trap to lower-than-normal trap-catch rates and thereby test the predicted possum recovery rates and associated effects of harvest on biodiversity values. The research team stresses that its findings only apply to the modeled system and cautions that these findings need to be extended to other forest types or harvest systems elsewhere in New Zealand.

This work was funded by the Ministry for Science and Innovation through Landcare Research Capability funding.