Communities, agencies and 1080

Pathways for New Zealanders to engage in decision making for pest management are currently quite limited. Diverse public interests are expressed via activities such as making submissions on pest management plans, attending public meetings about upcoming 1080 operations, protesting about the use of 1080, helping with ground control, and monitoring the impacts of pest control. Some people seeking to engage with pest control decision-making find these avenues inaccessible, non-inclusive and ineffective. While community engagements can lead to increased consensus around pest control, this is difficult to achieve. In New Zealand successful engagement processes are rare, usually small scale, and often lack adequate resourcing.

A team from Landcare Research, led by Alison Greenaway, are investigating the capabilities for enhanced community engagement in pest control decision-making. In a literature review undertaken in 2011, Alison found that controversies around pest control in New Zealand appear to be relatively well understood. The concerns stakeholders have about different control methods are well and consistently documented. However, despite having some understanding of each other’s positions, different stakeholders often do not accept others’ positions as valid.

Resourcing for effective community processes, in terms of people’s time, costs and skill levels, are high, as they require ongoing engagement rather than staccato bursts at decision-making moments. In addition, engagement is usually done at a small, community scale, and therefore, while the outcomes of the process may be highly successful, they are very limited in terms of the number of people affected. Added to this is the need for effective engagement to involve a degree of flexibility on the part of the agency managing the process, as the sought-after outcomes can conflict with the agency’s own culture and its actual or perceived remit. In addition, different stakeholders have different ways of describing engagement, participation, consultation, or dialogue, and their different uses of language can be confusing and hinder attempts at working across and between different groups.

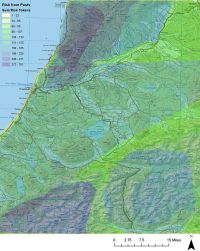

Participation is influenced by the interplay of relationships, issues, interests and environmental pressures. Also, there are many simultaneous interventions influencing site-based decisions. So the challenge is to position pest control decision-making practices amid all these other interests and activities shaping communities and places. Accordingly, Alison and her colleagues are working with individuals and organisations to try to enhance pest control decision-making as it happens, across scales and localities. One of the localities they are working in is Westland where there is a long history of discontent about the use of 1080. Between April 2013 and December 2013 the researchers undertook 29 semi-structured interviews involving people who live or work near Kumara or were known to be actively concerned about the use of aerial 1080 in Westland. Seventeen of these people also agreed to participate in an exercise mapping their perceived risks (identified by placing tokens on a map) from pests (Fig. 1) and pest management (Fig. 2).

In January 2014, some of the people interviewed were invited to a workshop in Hokitika where a range of objectives were investigated. For the researchers, the intention was to share findings and possibilities for enhanced engagements with people who were highly concerned about the use of 1080, and to discuss the science underpinning its use in New Zealand. Participants discussed specific questions raised in the earlier interviews including how bovine tuberculosis (TB) is detected, what TB testing methods are used in Westland, the impacts of 1080 on people, society and wildlife, and ideas for enhanced decision making. The ultimate purpose of the workshop was to create a unique forum for people with a diversity of perspectives, especially around the use of 1080, to meet and attempt to generate points of common interest.

The workshop generated three key ideas, which Alison and her colleagues will explore through a variety of avenues in 2014:

- Formalising a ‘watchdog group’ of community members that has some defined accountabilities and mandates. A likely outcome of the group could be a report each year for the media and key government agencies on whether local 1080 operations achieved their objectives and on other operational issues community members noticed.

- Supporting an independent citizen-science panel or jury comprised of citizens with a range of interests and concerns regarding pest control. Through meetings, fact-finding missions and workshops, this jury could come up with a checklist of questions, conditions, and targets for pest control operations in Westland. Thus, operations would be reviewed by independent panels of citizens in addition to current regulated procedures.

- Participatory planning of ground control. Currently, only landowners located within or adjacent to pest control operations are consulted when determining buffer zones around towns and water supplies. However, a series of public workshops could be planned in which the wider community could be invited to participate in assigning buffer zones to operations based on ground control instead of aerial control.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (C09X1007).

Alison Greenaway, Rebecca Niemiec & Bruce Warburton

Fig. 1 Citizens’ perceived risk from pests to ecosystems throughout the Hokitika and Kumara areas (based on assigned risk ‘tokens’ attributed by interviewees to areas threatened by pests).

Fig. 2 Citizens’ perceived risks from aerial use of 1080. Greatest risks were thought to occur to water catchments such as Lake Kaniere and the Kumara reservoir.