Economic instruments for management of mongoose in Fiji

The small Indian mongoose was first introduced into Fiji in 1883 to control rats in sugar cane fields and is now established on 13 of Fiji’s approximately 332 islands, including Viti Levu (1,038,700 ha), Vanua Levu (554,500 ha), and 11 small islands ranging in size from 6.9 to 17 ha.

Mongooses are agile predators: in addition to rodents, they feed on reptiles, frogs, birds,& invertebrates, and eggs. In Fiji alone, this invasive species has been implicated in the extinction or decline of barred-winged rail, Pacific black duck, banded rail, purple swamp-hen, white-browed rail, sooty rail, friendly ground dove, black emo skink, and Gibbons’ emo skink, ensuring its place among IUCN’s 100 worst invasive species. Mongooses also feed on fruit and vegetable matter – including crops – with at least 15% of their diet derived from these sources. In addition, mongooses are carriers of leptospirosis.

For these reasons, control of mongooses on the islands of Fiji and elsewhere has been under investigation since the 1950s. While bounties and trapping have been unsuccessful on islands larger than 115 ha, the species has been eradicated from at least six small islands via trapping and secondary poisoning. Nevertheless, the costs and benefits of such management are poorly understood.

Pike Brown, Adam Daigneault and Suzie Greenhalgh recently partnered with the University of the South Pacific (USP) and Pacific Invasives International (PII) to conduct cost–benefit analyses of mongoose control on Viti Levu, focusing explicitly on impacts that may be monetised. In total, 360 households in 30 indigenous Fijian villages were surveyed to quantify the value of livestock and fruit crops lost to mongooses and the time and money spent managing them. Results of the survey indicate that households that regularly keep chickens lose on average 6.5 per year to mongooses. Villagers in some areas also report that mongooses attack ripening fruit and vegetables.

In addition, respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed with a series of value statements pertaining to mongooses, e.g. ‘I would like to have more small Indian mongooses in this area’. Eighty percent of survey respondents viewed mongooses negatively, and 13% viewed them neutrally.

Despite the fact that respondents hold overwhelmingly negative views and that most villages report economic losses from mongooses, few survey respondents attempt to reduce the mongoose population. On average, households spend just 3.2 minutes per week trapping or hunting mongooses, and just 2% of households spend an hour or more per week on trapping or shooting. In contrast, the average surveyed household allocates 3.7 hours per week to managing the invasive African tulip tree.

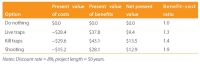

For the purpose of their cost–benefit analyses, Pike, Adam and Suzie considered four distinct options for managing mongooses: doing nothing, live trapping, kill trapping, and shooting. The costs associated with each management practice were derived from surveys conducted by the Fiji Ministry of Primary Industries. The effectiveness of each option was evaluated by colleagues at Landcare Research, PII, USP, and the Fiji Ministry of Fisheries and Forests. The team assumed a project length of 50 years and a discount rate of 8% – the median used for long-term environmental projects in the Pacific. Finally, the population of mongooses was assumed to follow a logistical growth curve, with the current population assumed to have already reached carrying capacity of 10 per hectare.

Cost–benefit analysis revealed that kill trapping using the DOC 250 trap is more cost effective than live trapping or shooting on a per hectare basis (Table). Indeed, given that about 6% of eastern Viti Levu’s 411,000 ha of land is currently under cultivation and the crops are at risk from attack by mongooses, the value of using kill trapping to manage mongoose is at least $FJD13.5 million over the next 50 years. However, kill trapping also entails comparatively high capital costs, and with its modest capital costs and high benefit-to-cost ratio, shooting is an attractive and less expensive alternative to kill trapping. Live trapping is less effective than kill trapping and less efficient than shooting, making it the third-best option. Nevertheless, all three management options are much more cost effective than doing nothing. Finally, these findings are robust to a range of assumptions regarding initial population, management effectiveness, and discount rates, and underscore the value of control.

This work was performed with financial support from the seven members of the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, namely, L’ Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the European Union, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the World Bank.

Pike Brown, Adam Daigneault and Suzie Greenhalgh