What motivates communities to create sanctuaries?

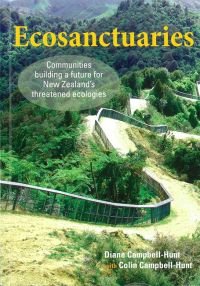

Rotokare Sanctuary - a predator-free fenced wetland and forest sanctuary in eastern Taranaki. Image – John Innes.

In increasing numbers, communities are launching projects aimed at protecting New Zealand’s native flora and fauna from the ravages of introduced browsers and predators. Such projects come in many forms: some specific to individual species, others aiming to restore entire ecosystems; some controlling a few predators, others building fences to eliminate them all. For many years, Landcare Research has supported a website and an annual workshop that brings sanctuaries together, and in 2013, Sanctuaries of New Zealand Incorporated (SONZI) was established to help these many initiatives learn from each other.

The Landcare Research sanctuaries database acknowledges 55 sanctuaries totalling 48,000 ha, of which 38 are community-led and total 25,000 ha. In practice, nearly all such projects are cooperative. The mean number of partners in sanctuaries, excluding funders, is 3.2 (range 1–8) and the Department of Conservation (DOC) is a partner in 42 (76%). In total, 42 species have been translocated into 20 community-led sanctuaries, including 31 birds, 6 reptiles, 2 insects, 2 fish and a frog.

These projects are an important new contribution to the conservation cause. So what is driving their establishment? First and foremost, every one of the thousands of people caught up in this movement is deeply concerned for the future of New Zealand’s native species and wants to do something directly and personally to halt their decline and to restore at least some semblance of the way New Zealand was before people came. Many of the founders have close ties to the land, e.g. local landowners and tangata whenua.

These people are inspired to recreate, even on a small scale and imperfectly, ecosystems that have vanished from the mainland over the centuries of human habitation. They want to hear New Zealand’s birds singing again, to walk through bush where native birds once again thrive, free of imported mammalian mastication and predation. Their greatest hope is to see sanctuaries lead a change in public attitude to conservation such that, in time, the whole country might be free of the worst predators.

You could say that it is local communities that have brought these projects to life. But it is just as true that these projects have been the means for creating communities with a shared commitment to the conservation cause. These groupings have a shared vision to restore what they can of what has been lost, and aim to use the beauty of these lost worlds to advocate for conservation. They want children to experience New Zealand the way it was, to make their native world part of their identity as New Zealanders.

What does it take to get these projects going? Often, it seems that key individuals emerge to galvanise others with their vision and drive. These special people are passionate about conservation but they also have the ability to create a community of supporters that will bring the project to life. There is a social ecology on which the restored natural ecology depends. Evidence of support from the community is usually important in attracting financial support from local councils and trusts, and sustained profile in local media keeps the project in the public’s mind.

For a community to come together in this way, it needs to feel a sense of ownership of the project. For larger projects, this can mean the formation of a trust to manage the sanctuary. The people involved in these sanctuaries want to make a direct, personal contribution and to share that contribution with others they come to know as friends: a sanctuary family. Without the freely-given efforts of volunteers, and the financial support of local trusts and memberships, sanctuary projects cannot be sustained. The participation of tangata whenua is of special importance, in part because of the role they play in species translocations.

The belief is that by tapping into these powerful motivations of shared personal commitment, community-led sanctuaries are bringing resources to the conservation cause that would otherwise lie dormant. The recent repositioning of DOC has explicitly recognised the emergence of community-led sanctuaries and is aiming to forge partnerships with them, seeking perhaps to leverage the limited resources DOC has available to advance the conservation cause.

This work was funded by the Tertiary Education Commission through a Top Achievers PhD scholarship, with additional funding from Landcare Research and the University of Otago.

Colin Campbell-Hunt, University of Otago

Contact: ccampbellhunt@gmail.com

John Innes

Coriine Watts and Danny Thornburrow collecting Mahoenui giant weta from the Mahoenui giant weta scientific reserve for translocation to Maungatautari Ecological Island, April 2012. Image - Jocelyn Neville

Measuring the hind leg of a Cook Strait giant weta before translocation to Zealandia, a sanctuary in Wellington. Hind leg, pronotum (segment behind head) width and weight of every weta were recorded. Image – Danny Thornburrow.

Colin Campbell-Hunt is co-author with his late wife Diane of ‘Ecosanctuaries: Communities building a future for New Zealand’s threatened ecologies’,Otago University Press, 2013.