Pollen and spores

Preserved pollen and spores are extracted from peat or sediment cores, counted under a microscope, and used to discover what plants were growing on the landscape in the past.

What are pollen and spores?

Seed-producing plants (the angiosperms and gymnosperms) produce vast numbers of pollen grains, which form in the anthers and contain the male gamete part of the plant. The pollen grains need to reach the stigma, the female part of the plant, in order for fertilisation to take place to produce new offspring. Ferns, mosses, and other lower plants produce spores instead of pollen to reproduce. Spores are also released in huge numbers, but all they need to do is be dispersed to a suitable habitat and they can grow into a new plant.

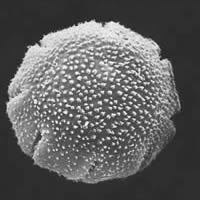

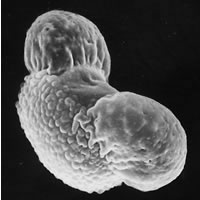

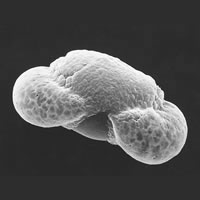

Pollen and spores are extremely small. You might have seen a greenish powdery substance at various times of the year collecting in the gutters, on your car, or being blown across valleys on a windy day. Chances are that what you are seeing are millions of tiny pollen grains blowing around in the wind. On closer inspection under a microscope you can see that they vary in size (7–100 micrometers) and structure. It is the unique structuring patterns on the exterior wall of pollen grains and spores that allows us to identify most of them to species, or in some cases to their genus or family. In New Zealand our largest pollen grains are from the tall forest tree miro (Prumnopitys ferruginea); the smallest from a forget-me-not (Myosotis). Tree ferns and many ground ferns typically produce rather large and robust spores.

Pollen and spores

|

|

|

| Silver beech | Totara | Matai |

|

|

|

| Grass | Bracken | Willow |

Pollen structure may relate to how the plants are pollinated, whether by wind, water, insects or birds. For example, the pollen of species that are insect pollinated are often sticky or spiny, whereas wind-pollinated species may produce smooth pollen (e.g. the grasses), or pollen with air sacs and a low specific gravity (e.g. podocarp trees like tōtara, miro, mataī and kahikatea) to make them more buoyant and able to blow long distances in the wind. Wind-pollinated plants tend to produce more pollen than insect- or bird-pollinated plants, as they have a harder time trying to land on receptive stigmas.