Community responses to livestock removal from drylands

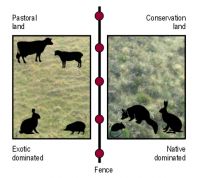

Cartoon – Susan Marks.

Sheep and cattle are known to affect native vegetation in drylands by browsing or trampling, reducing seedling recruitment and increasing the abundance of exotic plants. Managers often assume that removing livestock will reverse such processes, leading to the recovery of native biodiversity. However, plant communities are complex and the removal of grazing pressures may result in unexpected changes to community diversity and structure. For instance, a dense sward of exotic grasses may form after the removal of livestock if such grasses are more competitive than native shrubs. Sites retired from grazing may also be more attractive to invasive mammals, requiring more active management to attain positive conservation outcomes.

The variable nature of community responses to livestock removal make it difficult for conservation managers and policymakers to plan for the long-term impacts of a change from pastoral to conservation land. To manage former pastoral lease land for conservation, it is important therefore to clearly identify the potential responses of native communities to livestock removal, and the mechanisms that drive these changes.

Amy Whitehead and colleagues set out to investigate the impacts of livestock removal on mid-altitude dryland communities, by comparing the presence and abundance of plant and invasive mammal species on cur-rently grazed sites with that on conservation sites where pastoralism ceased 10–40 years ago. Areas were chosen on four properties in the eastern South Island where paired pastoral and conservation sites were separated by fences.

Removal of livestock had little impact on the number of plant species present on either side of the fence. However, the composition and structure of these plant communities differed significantly (Fig.). Sites on conservation land had higher native biodiversity, with small native herbs, grasses and shrubs more abundant than on the adjacent pastoral sites. Sites on pastoral land were dominated by exotic plants, particularly herbs and grasses. Exotic grasses had a negative impact on native biodiversity on both sides of the fence but the effect was stronger on pastoral land. The exotic weed Hieracium was equally abundant on both pastoral and conservation land, while native shrubs were more abundant than exotic shrubs on conservation land. Amy believes these changes indicate that the study sites are undergoing successional changes towards a native-shrub-dominated ecosystem after the removal of livestock.

The change in tenure from pastoral to conservation land also had an impact on the invasive mammal communities present. Rabbits and hedgehogs were more abundant on pastoral sites, while possums, hares and mice were more abundant on conservation sites. Rabbits have a preference for short-grass habitats, while hedgehogs may be attracted to areas with animal dung containing abundant invertebrates such as fly larvae and earthworms. By comparison, invasive mammals found on conservation land were generalist species, attracted to structurally complex and diverse habitats. It is not clear whether these patterns are driven ‘bottom-up’ (i.e. by invasive mammals responding to available resources) or ‘top-down’ (i.e. by invasive mammals effectively engineering suitable habitat for themselves), or a combination of both.

Overall, removal of livestock led to the development of native-dominated plant communities, with a high abundance of shrubs. This has positive implications for conservation, as the low abundance of exotic weeds means there may be little need for active weed management. However, this outcome may be compromised by increases in the relative abundance of some invasive mammal species (see article by Norbury et al.).

This work has been funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Programme C09X0909) and Landcare Research’s Capability funding.