Growth rates and recruitment of native shrubs on retired Crown land

Contrast between retired Crown land (Matata Reserve, right) and pastoral land (Mt Nimrod Station, left) in South Canterbury. Image – Andrea Byrom.

The effect of the removal of livestock on the diversity of native plant communities in the South Island’s subalpine drylands (~1000m altitude) is discussed elsewhere in this newsletter (see Whitehead et al.). Here, Andrea Byrom and colleagues explore another important aspect of the effect of removing livestock: the recruitment and growth of shrubs.

A characteristic of these grasslands is their tendency to revert to woody vegetation. But how exactly do shrubs respond when exotic grazers are removed? Quantifying shrub recruitment and growth is an important first step in determining the role that woody vegetation plays in the conservation of biodiversity of retired pastoral land and how this may change with time through shrub succession. Shrubs potentially provide food and shelter for native fauna such as lizards and invertebrates. However, they also harbour invasive mammals such as mice and possums – species that prey on native fauna, and impact on native vegetation. The carbon sequestration potential of this land through reversion to a woody flora is also increasingly relevant, as New Zealand has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Andrea and colleagues worked on the same properties mentioned in Whitehead et al.; each of the four areas contained grazed sites paired across fence lines with ungrazed sites where pastoralism had ceased 10–40 years ago. They concentrated on two native shrub species: matagouri and mānuka, and hypothesised that both species would have greater recruitment and growth rates in destocked areas.

Samples of up to 30 randomly located individuals of both mānuka and matagouri were cut from all eight sites and shrub age estimated by counting growth rings of stem sections. The team also measured stem diameter, and plant height, volume and biomass. On some sites, fewer shrubs were sampled, but the researchers were able to back-calculate the ages of all individuals by developing allometric relationships between age (growth rings) and stem diameter of the shrubs that were ‘sacrificed’.

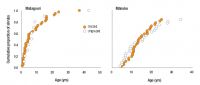

Surprisingly, Andrea’s team found no evidence that removal of livestock had any long-term effect on the recruitment of either mānuka or matagouri (Fig. 1). If their hypothesis was correct, they would have recorded pulses of recruitment on sites with no livestock, but this was not so – individuals of both these species recruited onto grazed and ungrazed sites at the same rate, at least over the 40-year time frame of the project.

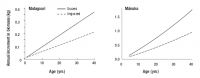

Age was very strongly correlated with stem diameter, height, volume and biomass for both mānuka and matagouri. Regardless of which of these growth variables was measured, the effect of grazing by livestock was counter-intuitive: growth rates were actually higher on grazed sites (Fig. 2). In other words, plants on grazed sites were larger for their age than those on the ungrazed sites.

The findings of Andrea and her colleagues suggest that in mānuka- and matagouri-dominated seral plant communities in drylands, moderate grazing pressure from livestock may have very little effect on recruitment of shrubs. Also, while removal of grazing slows shrub growth in a 10–40-year time frame, previously grazed populations of adult shrubs can provide new recruits during reversion to shrubland. One possible explanation for the lack of difference in shrub recruitment on grazed and ungrazed sites is that grazing by livestock reduces competition from exotic grasses, thereby allowing small shrubs to establish, effectively ‘cancelling out’ any direct effect of grazing on the shrubs themselves.

These findings have important implications for the management of seral shrubland communities. In many parts of the drylands, plant communities are subject to occasional grazing, e.g. during short-term grazing leases, and to other forms of moderate to low-level grazing. While these findings apply to just two species of plants, both of which are relatively unpalatable to livestock, managers can be cautiously optimistic that grazing by ivestock is not necessarily all bad for shrub retention and recruitment. Of course, over longer time frames or with longer periods of intensive grazing, and for different native shrub species, the effects of grazing may be more severe and potentially irreversible.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Programme C09X0909) and Landcare Research Capability funding.

Andrea Byrom, Richard Clayton, Roger Pech, Peter Williams & Guy Forrester

Fig. 1. Recruitment of matagouri and mānuka on grazed and ungrazed sites. The plots show the cumulative proportion of shrubs recruitedat a given age, and revealed there was no difference between pastoral and conservation sites for either species.

Fig. 2. Growth of matagouri and mānuka on grazed and ungrazed sites. Both species showed faster growth rates on grazed sites compared with sites where livestock had been removed for 10–40 years.