Possum ecology: diet, home range, movement patterns and denning

Carlos Rouco downloading GPS data from a recaptured collared possum. Image – Heléne de Meringo.

Little is known about the ecology of possums in New Zealand’s drylands, despite possums being common there and subject to control over vast areas to mitigate their spreading of bovine TB. Here, Carlos Rouco and Al Glen describe studies of possums in two dryland regions of the South Island. On Molesworth Station they examined the summer diet, feeding preferences, denning behaviour and survival rates of possums, while in Central Otago they studied possum densities, denning behaviour, and home ranges.

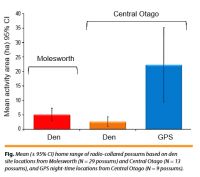

The summer diet of possums at Molesworth was dominated by forbs and sweet briar, both of which were eaten in large amounts relative to their availability. Possums also strongly preferred crack willow, which was uncommon in the study area and eaten only occasionally but in large amounts. Dens of 29 radio-collared possums were mostly found under sweet briar, followed by in or under rocky outcrops. Activity areas of possums based on den locations varied from 0.2 to 19.5 ha (mean = 5.1 ha). Annual survival of radio-collared individuals was 85% for adults and 54% for subadults.

In Central Otago, population estimates were derived from capture–mark–recapture methods at two sites: one with higher shrub cover (51%) than the other (20%). Possum densities were greater at the high-shrub-cover site (1 per hectare, 95% CI 0.80–1.26 ha) compared with that at the low-shrub-cover site (0.54 per hectare, 0.42–0.67 ha). Moreover, possums were significantly heavier at the high-cover site. Because shrubs such as sweet briar are an important source of food and shelter for possums, their availability is likely to play an important role in determining possum carrying capacity.

Fourteen adult possums were radio-tracked at the high-shrub-cover site. Shifts in den sites were very frequent, with the maximum number used by a single possum being 26 (from 31 location fixes). Rocky outcrops were more common in this region compared with Molesworth, and most dens (61%) in Central Otago were in or under rocks, 34% were under shrubs, and 4% in rabbit burrows. Home ranges based on den site locations were similar to those at Molesworth but were larger for possums living in open areas compared with those living in gullies (6.8 and 0.9 ha, respectively). In Central Otago, home ranges based on night-time activity were 10 times the size of those based on den locations (Fig.).

The ecology of possums in these two study sites differed from that of other studies of possums in forest or farmland habitats. Possum densities in drylands were 3 to 13 times lower than those estimated for mixed podocarp–broadleaved forest, but were similar to those recorded in Pinus radiata or beech forest. Home ranges in drylands were similar to those recorded in farmlands (26–31 ha), but larger than those recorded in mixed podocarp–broadleaved (0.5–3.9 ha), Pinus radiata(0.7–1.4 ha) or beech forest (1.7–5.6 ha). Carlos and Al believe such differences reflect the generally lower availability and more patchy distribution of resources in drylands. Their results suggest that invasive willow and sweet briar may facilitate possum abundance by providing abundant food and shelter. This information will be useful for modelling and managing the impacts of possums in dryland habitats, and should increase the efficiency and effectiveness of ground control of possums there.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Programme C09X0909: Invasive Mammal Impacts on Biodiversity).