Impact of rabbits (and sheep) on drylands

Regional pest management strategies for rabbits set indices of rabbit density above which landowners are generally obliged to conduct rabbit control. Most strategies set these trigger points at an index of 3–4 on the McLean’s Scale (an exponential index of 1 to 10 based on rabbit sign). In the Mackenzie Basin, a McLean’s Scale Index of 3 translates to about 2 rabbits/km and an index of 4 equates to about 8 rabbits/km on the alternative spotlight-count index. While the relationships between the indices and actual rabbit densities are unclear, these trigger indices are based on the expectation that rabbits at such densities (and before the outbreak of rabbit haemorrhagic disease) rapidly increase to very high levels unless control is instituted. If the decision to control is left too late, the costs of control are substantial.

Such input-based justification for control is weak when arguments arise as to the real benefits of rabbit control. Surprisingly, few people have measured the effect of changing rabbit densities on vegetation growth, at least in the rabbit-prone drylands in the eastern South Island. John Parkes and colleagues set out to remedy this: they measured vegetation growth across seasons at six sites in three places in Otago using a series of plots that allowed access by both rabbits and sheep, just rabbits, and neither rabbits nor sheep. The team knew the density of sheep at each site and indexed rabbit density (rabbits/km) on spotlight routes across the sites. They then used the data to model the effects of changing rabbit and sheep numbers on the seasonal growth rate of the vegetation.

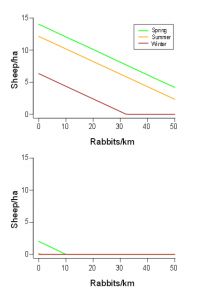

To illustrate model predictions, on the two most degraded sites (in the foothills of the western Dunstan Mountains), if there were neither sheep nor rabbits present, pasture biomass was predicted to grow in spring, just grow in summer, and decline in winter. If there were no sheep but the number of rabbits varied from 5, 10, and up to 50 rabbits/km, then pasture growth was predicted to stop in summer at 5 rabbits/km, almost stop in spring and decline in summer and winter at 10 rabbits/km, and not grow in any season at 50 rabbits/km. This same pattern was revealed at the less degraded sites in the foothills of the Old Woman Range and in eastern Otago at Macraes Flat, although the model predicted some pasture growth in spring and summer even at 50 rabbits/km.

John’s team also used the model to predict maximum stocking rates for sheep in each season given different rabbit densities but still allowing for at least zero or some pasture growth. On the most fertile site, some sheep could be grazed even where rabbit densities exceeded about 30 per kilometre, except in winter. On the least vegetated site, a few sheep could be grazed where densities were below 10 rabbits/km but only in spring (Fig.).

Using this approach, for example, a farmer that needed at least 5 ewe-equivalents/ha to farm profitably, and did not wish to see a reduction in pasture biomass between years, could achieve this stocking rate year-round on the most productive dryland sites studied if rabbits were held below about 5 per kilometre, but only in the spring on the least productive sites. Therefore, as a rule of thumb, setting intervention triggers at McLean’s Scale 3–4 seems about right for land with moderate amounts of vegetation but is unlikely to allow badly degraded land to recover, or to support sustained sheep grazing at economic stocking rates.

The team next seeks to partition pasture growth by species (palatable and unpalatable) and turn their estimates of benefit (ewe-equivalents/ha) into some measure of on-farm economic benefit (the value per stock unit) to compare with the costs of various forms of rabbit control. This approach will demonstrate whether control on one part of the farm is being ‘subsidised’ from other parts of the farm or requires input from external funders, and whether investment in research to make rabbit control (especially expensive aerial poisoning, which is required for rabbits at high densities) more efficient and so reduce the need for subsidies.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation.