What drives the dynamics of indigenous and invasive fauna in grassland ecosystems?

The three habitat types studied at Macraes Flat: degraded herbfield (left), intact tussock (middle), and mixed shrubland (right). Images – Grant Norbury

At Macraes Flat in eastern Otago, DOC staff are controlling cats, mustelids and hedgehogs over 4,600 ha of degraded herbfield, intact tussock, and mixed shrubland to protect critically endangered skinks. Grant Norbury and colleagues are concurrently studying the population responses of other species in these same sites – common lizards, invertebrates (including weta), mice and rabbits – to test the following hypotheses:

- Invasive predators are the primary drivers of indigenous fauna and invasive herbivores

- Impacts of predators are greatest towards the edge of a control zone (where invasive immigrants abound)

- Structurally complex habitats support more abundant fauna

- Mice negatively affect indigenous fauna

The work began with a pilot study in December 2010. Grant and his team randomly selected 48 grids, 45 x 45 m, stratified by the three habitat types. Tracking tunnels, artificial refuges, and rabbit faecal pellet plots were set on each grid. DOC’s records of the numbers and locations of predators kill-trapped since 2006 were used to show where predators were distributed across the landscape – the team assumed that high captures of predators refl ected their high abundances.

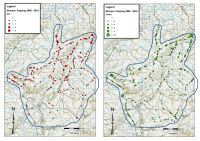

Ferrets and weasels were caught mostly towards the edge of the control area, while cats were caught mostly in the northern half (Fig. 1). The grids were therefore classified into five zones: northern half, southern half, outer edge, inner core, and in between the edge and inner zones. The north was surrounded by developed pasture and this benefited rabbits, which are the primary food source for predators in this system.

Indigenous fauna are often secondary prey for predators in dryland ecosystems and this can make them particularly vulnerable to population depletion and even localised extinction. The tendency for more predators to be captured towards the outer edge and the north would therefore suggest that indigenous fauna will be less abundant there. However, this was not the case. Lizard captures (in artificial refuges), for example, were similar in each zone (Fig. 2) as werecaptures of weta and other invertebrates.

Habitat type appeared to strongly affect some fauna – mice were only ever detected in shrub habitat (but only in a small proportion of sites), and geckos were often more abundant there (provided mice were absent) (Fig. 3). Rabbits showed the opposite pattern – they were least abundant in shrubland and most abundant in degraded herbfield (although not significantly so).This isn’t surprising as rabbits are known to prefer more open and simplified habitat (see article by Whitehead et al.).

A controversial issue at Macraes Flat is whether predator control has led to an increased abundance of rabbits. The team’s data do not support this. Significantly more rabbit faecal pellets were found in the northern zone (89 per plot), where predators are generally more abundant, than in the southern zone (21 per plot). Rather than predators driving the rabbits ‘top-down’, it appears that the rabbits are driving the predators ‘bottom-up’. Rabbits are in turn driven ‘bottom-up’ by the development of their preferred pasture habitat in the north. Experiments elsewhere also show that removing rabbits leads to declines in predator numbers.

Mice are also predators (and potential competitors) of lizards and invertebrates but little is known of their impacts in grasslands. Grant’s team were unable to measure mice impacts directly, but there was some evidence of predation or competition by mice from the negative relationships between mice and lizards, and between mice and invertebrates (Fig. 4). Lizard and invertebrate abundances varied greatly where mice were not detected, but they were always uncommon where mice were detected, indicating that mice may be detrimental to populations of some indigenous species.

These results suggest that for relatively common fauna at Macraes Flat, bottom-up effects associated with habitat type may be stronger than top-down effects of top predators. Succession of grasslands to mixed woody shrublands may be the key driver of remnant fauna in this system. Given that mice are expected to benefit from succession, understanding their functional role in these ecosystems is critically important.

This work is funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Programmes C09X0909 and C09X0505), and in-kind funding from the Department of Conservation.

Grant Norbury, Deb Wilson, James Smith, Dean Clarke, Andy Hutcheon, Roger Pech & Andrea Byrom

Fig 1. Kill sites of predators at Macraes Flat during 2009–2010. More cats were killed (left) in the northern half of the trap area, and a similar pattern pertained for ferrets, although they were more concentrated around the edge (right).

Fig 2. Numbers (mean ± 95% CL) of common lizards captured per grid in the core versus the edge (top), and in the north versus the south (bottom), of the predator control area.

Fig 3. Numbers (mean ± 95% C.L.) of geckos (left) and rabbit faecal pellets (right) per grid in each habitat.

Fig 4. Mouse tracking rates and numbers of lizards (top) and invertebrates (bottom).