Assessing the suitability of citizen science data for biodiversity reporting

Mahoenui Giant Weta. - Rita Bruce-Nanakeain

Biodiversity reporting is concerned with assessing or monitoring the status and trends of species over time. Monitoring can be thought of as either structured or unstructured. In structured monitoring surveys are performed at randomly selected sites using a consistent and repeatable methodology, typically by research technicians. A limitation of structured monitoring is that it is expensive and time consuming, and as a result only a limited number of locations can be monitored.

Over the past few years there has been a vast increase in the amount of species observation data gathered by members of the public (as opposed to professional technicians). Citizen science, as it is often called, is public participation in scientific research, whereby non-scientists take part in some aspect of science, most commonly the collection of data. There are many reasons why citizen scientists collect and enter observational data, including having a place to reliably store their own records or contributing to some larger database.

Monitoring by citizen scientists is often unstructured: individuals visit locations of interest to them and use their own survey methods. It is undeniable that these data repositories contain a lot of rich information; what is less clear is whether these data can be used to provide robust inferences about species distribution and changes.

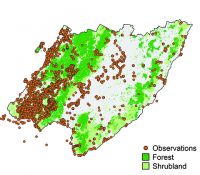

Andrew Gormley and Catriona MacLeod have worked with the Greater Wellington Regional Council to assess the suitability of citizen science data for reporting on birds in the Greater Wellington region. They looked at the data contained in New Zealand (NZ) eBird, an online checklist program jointly administered by Birds New Zealand and the Cornell Laboratory for Ornithology, which enables a wide range of users to submit bird observations into a secure database. The volume of NZ eBird data from within the Greater Wellington region is vast, with 13,560 separate observation events from 2008 to 2014 (Figure 1). Andrew and Catriona identified a number of issues that can arise when attempting to aggregate unstructured data into a reporting metric and presented a number of solutions to partially mitigate these issues, as well as some recommendations for future data collection.

Aggregating unstructured data: issues and solutions

Unstructured data can suffer from a number of issues relating to the observation process (e.g. where we looked, how hard we looked and what we looked for) , including pseudo-replication, species reporting bias and spatial bias.

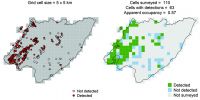

Pseudo-replication occurs when the same thing is measured multiple times. If multiple people carry out bird observations in the same location, then the records are not independent and cannot be treated as such. This issue arises in the NZ eBird database because observers tend to make observations close to where they live, resulting in the majority of records being around major cities and towns (Figure 1). One method to partially solve this is to aggregate the observations into spatial units (or grid cells) and report on the proportion of grid cells a species has been detected in (Figure 2).

Species reporting biases can occur when species are recorded in a manner that has little to do with their distribution or abundance and more to do with other characteristics. People will generally tend to record observations of species that are rarer and less widespread. There may also be a bias towards native/endemic species compared to introduced species. One potential solution with the current NZ eBird data is to use only records where observers indicated that they recorded every species present and that were able to be identified.

Spatial bias occurs due to observers favouring locations that are close to where they live. The majority of NZ eBird observations between 2008 and 2014 are located in the western half of the Greater Wellington Region and are highly clustered, with many records close to major populations (Wellington, Lower Hutt, Upper Hutt), and comparably few in the east of the region (Figure 1). Any species that is common in the east will be recorded less often and will therefore be assumed to be less common than a species that is common in the west and therefore observed and recorded more often. Furthermore, if the sampling distribution changes over time (e.g. increased sampling in the east), this may result in a change in the proportion of observations that contain species with an uneven spatial distribution, even if the distribution of those species remains constant.

A related issue is representativeness. The paucity of records in the east means that any inference about birds from the data may not apply to the entire Greater Wellington region. Structured surveys do not survey every possible location, but sampling locations are chosen so as to remove the influence of the technicians and to ensure the set of locations are representative of the entire region. For the current data set Andrew and Catriona recommended narrowing the focus to only making inferences about sub-regions where there was suitable spatial coverage, such as around Wellington City.

Unstructured data, such as the observation records in NZ eBird, are arguably as reliable as any that would result from monitoring by research technicians, especially considering the skills and vast experience of many of the citizen science observers. It can therefore be assumed that if a record in a citizen science database includes an observation of a specific species, then that species was indeed detected. Issues with unstructured data arise only when attempts to aggregate them into a metric are made for reporting purposes.

A more structured approach to the survey effort, with observers using standardised monitoring methods, would greatly increase the coverage and value of the data gathered. This could result in large numbers of records from many skilled observers, with the data gathered in such a way that when combined they are unbiased and representative of the entire region. The challenge for the future is how to achieve this level of coordination to fully realise the potential value of the data.

This work was funded by the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment as part of the Building Trustworthy Biodiversity Indicators project (C09X1308) and Greater Wellington Regional Council, with in-kind support from Birds New Zealand.

Andrew Gormley, Catriona MacLeod

Figure 1. Bird observations contained in NZ eBird from the Greater Wellington Region from 2008 to 2014.

Figure 2. Raw data of detections and non-detections of tūī in 2012 from NZ eBird, and aggregated 5 km × 5 km grid cells, with each cell classified as detected, not detected or not surveyed.