What is happening with wallabies in mainland New Zealand?

ive species of wallaby have been present in New Zealand for over 140 years, with populations centred in South Canterbury (Bennett’s wallaby), Rotorua (dama wallaby) and Kawau Island (dama, parma, brush-tailed rock, and swamp wallabies). Since their initial releases wallabies on the mainland have increased in numbers and distribution, and they compete with livestock for pasture, browse seedlings in plantation forests and damage indigenous vegetation.

ive species of wallaby have been present in New Zealand for over 140 years, with populations centred in South Canterbury (Bennett’s wallaby), Rotorua (dama wallaby) and Kawau Island (dama, parma, brush-tailed rock, and swamp wallabies). Since their initial releases wallabies on the mainland have increased in numbers and distribution, and they compete with livestock for pasture, browse seedlings in plantation forests and damage indigenous vegetation.

As part of their Regional Pest Management Plans, regional councils troubled by wallabies seek to keep them at low abundance, prevent their spread outside delineated containment areas, and, where they have spread, eliminate isolated populations. In recent years, however, numerous sightings of wallabies have been reported from outside such containment areas; for example, Bennett’s wallaby has dispersed south of the Waitaki River, a natural barrier which prevented their spread for many years. Concern at the ongoing spread of wallabies has prompted affected regional councils and the Ministry for Primary Industries to request a review of the extent of the current spread of wallabies and to predict what their future distribution will be if they are not adequately contained. The review was carried out by Dave and Cecilia Latham and Bruce Warburton.

To ensure councils’ needs were met, a steering committee was formed, with representatives from Environment Canterbury (ECan), Bay of Plenty Regional Council (BOP), Waikato Regional Council (WRC) and the Department of Conservation (DOC). This committee, along with Landcare Research staff, identified four desktop-based objectives:

- to update the current distributions of Bennett’s and dama wallabies

- to estimate current rates of spread of both species and predict their distributions in 50 years

- to describe the extent of suitable habitat for each species on mainland New Zealand

- to conduct a simple cost–benefit analysis comparing the cost of the impacts of Bennett’s and dama wallabies with the cost of different management strategies over the next 10 years.

The committee assisted with gathering the necessary data to support the analyses required, including incidental observations of wallabies, locations of animals shot outside containment areas, faecal pellet counts, and historical wallaby distributions.

At present, ECan estimates that Bennett’s wallabies occupy about 5322 km2 in the South Island. However, the large number of confirmed sightings and animals shot outside this area suggest they may currently occupy as much as 14 135 km2. BOP and WRC estimate that dama wallabies presently occupy about 2050 km2 in the North Island, but confirmed sightings outside this area indicate this figure could be as high as 4126 km2.

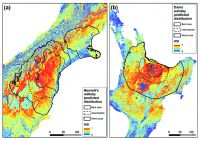

Using natural rates of spread estimated from historical distributions, the distribution of Bennett’s wallaby in 50 years is predicted to be between 9621 km2 and 20 631 km2, but possibly as much as 44 226 km2 if the spread from recent illegally liberated populations is included (see Figure). In the North Island the distribution of dama wallaby in 50 years is predicted to be between 3265 km2 and 11 070 km2, but possibly as much as 40 579 km2 if the spread from recent confirmed sightings from outside the currently delineated distribution is included (see Figure). Under the worst-case scenarios, wallabies could occupy one-third of each island. Further, within these future predicted distributions, habitat suitability models suggest there is ample good habitat for wallabies yet to occupy (see Figure). The areas they are likely to be absent from are high elevations, urban areas, and high-production exotic grassland (e.g. dairy farms), which have little cover for wallabies.

The team’s simple cost-benefit analysis suggests there is a large net economic benefit from the widespread control of Bennett’s and dama wallabies as opposed to doing nothing (i.e. the status quo of patchy control by landowners). However, the net benefit of containing them would be even greater. In quantitative terms, the team estimated that intensive widespread control and surveillance of Bennett’s wallaby within a containment area over 10 years would cost about $6.2 million, which represents one-third of the expenditure and revenue lost if they were allowed to expand their range for 10 years before control was applied ($18 million), or one-seventh the revenue lost if allowed to expand their range in the absence of management ($43.4 million). For dama wallabies, intensive widespread control and surveillance within a containment area over 10 years would cost about $3.4 million, which is half the estimated expenditure and revenue lost if they were allowed to expand their range for 10 years and then controlled ($8.6 million), or one-third the estimated revenue lost if they were allowed to expand their range in the absence of management ($12.3 million).

There is an obvious net benefit from controlling wallabies, particularly if they are contained to prevent impacts to habitats in areas that could be invaded. Regional councils’ attempts to contain them within delineated areas have not been successful, because new populations of both Bennett’s and dama wallabies have been detected well outside these areas. Furthermore, illegal liberations outside containment areas have resulted in a number of established populations, adding to the complexity of wallaby range expansion. New surveillance and detection tools and further information on the species biology, applied within an appropriate control or eradication framework, may help to halt current wallaby range expansion.

This work was funded by the Ministry for Primary Industries.

A. David M. Latham, M. Cecilia Latham, Bruce Warburton