Regional-scale biodiversity restoration in Hawke’s Bay: towards a predator-free New Zealand

The Cape to City programme (http://capetocity.co.nz/) in Hawke’s Bay is the largest wildlife restoration project across a primary production landscape in New Zealand, and the hope is that it will become a template for the large-scale restoration of New Zealand’s unique biodiversity. This is especially important given New Zealand’s recently announced goal of eradicating rats, possums and stoats by 2050.

Predator control and ecosystem restoration are usually confined to individual reserves and sanctuaries. Cape to City encompasses 26 000 ha of private and public land between Hastings and Cape Kidnappers, and extends south to include Waimarama and forest remnants at Kahuranaki. Most of it is productive farmland, and it involves 120 landholders. The aim is to allow native species to ‘thrive where people live, work and play’, and to see biodiversity, economic and social gains.

The work is a $6 million collaboration and joint funding venture between the Aotearoa Foundation ($2.3 million), Department of Conservation (DOC, $1.6 million), Hawke’s Bay Regional Council (HBRC, $1.5 million) and Landcare Research ($0.7 million). Iwi and landowners are also key partners in the programme. Cape Sanctuary on the Cape Kidnappers peninsula is also spending $0.6 million annually on biodiversity protection.

An extensive research platform underpins most activities, providing an evidence-based approach to management. The results of the work are published in peer-reviewed literature, and the programme involves the training and development of students. The work builds on a pre-existing predator control programme nearby called Poutiri Ao ō Tāne on 8000 ha of productive land around the Boundary Stream Mainland Island (a public reserve), which showed that wildlife in scattered bush remnants can be protected if predator control is widespread. But in order to scale up to 26 000 ha, the costs of predator control must be ultra-low.

Smart strategy

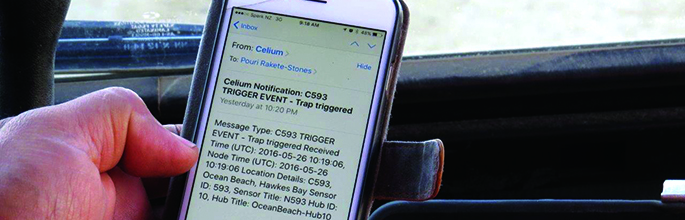

Kill traps are being deployed across the Cape to City area to control feral cats, stoats, ferrets and hedgehogs. Rats are controlled only in selected areas or in particular habitats. Predator control costs are reduced through a wireless network of predator traps. Electronics attached to each trap send a signal to the cellular network and then on to the landholder’s cell phone to indicate when and where traps are set off and need re-setting. Former Federated Farmers president Bruce Wills, who is on the Cape to City board, said time-efficient methods such as cell phone alerts when a trap is triggered mean farmers will support the programme.

Landcare Research scientists have modelled the optimum density of traps required to maximise captures. They have also modelled the effects of some landholders not participating in predator control. While almost all landholders are participating, a few are not. The modelling shows that placing additional traps on neighbouring properties can help offset the effects of the small number of non-participating farmers.

It is essential to know that trapping is successfully supressing predator numbers. However, monitoring the numbers of predators on such a large scale is challenging. Landcare Research is deploying motion-triggered cameras across the landscape in areas with and without predator control. This should provide sufficient data to estimate residual predator densities and therefore trapping success.

Measuring up

Monitoring changes in native biodiversity is an essential component of the Cape to City programme. HBRC biosecurity advisor Rod Dickson said monitoring had shown that native lizard numbers at Poutiri Ao ō Tāne have ‘gone through the roof’ since pest control began compared to a similar area nearby without predator control.

The abundance of birds, lizards and invertebrates in the Cape to City pest control zone, and in a large, adjacent non-treatment area, is being measured using modified 5-minute bird counts, artificial refuges for lizards, tracking tunnels, wētā houses, tree wraps, and funnels that collect invertebrate faeces (frass) dropping from tree canopies. Additional research involves exploring the use of genetic techniques, called ‘environmental DNA’, for improving the ability to record the diversity of invertebrate species.

Wildlife monitoring is also taking place along the Maraetotara River where habitat restoration is combined with predator control. The Maraetotara Tree Trust, with support from HBRC and the DOC community fund, plant native species along this river system every year to restore habitat for wildlife.

The hope is that predator control will not only help the recovery of wildlife in the Cape to City area, but also native birds, such as robins, tomtits, pāteke (brown teal) and kākāriki that fly out of the Cape Sanctuary every year. Previously these emigrants stood little chance of survival outside the sanctuary in an environment full of predators. DOC is also translocating robins and tomtits to Cape to City, and pāteke and petrels to Poutiri Ao ō Tāne. The survival of these species is an important litmus test of the success of the predator control programme.

As a consequence of this control, Rod Dickson reports that tomtits and robins have started to turn up at Te Mata Peak, while Dave Carlton, DOC’s Hawke’s Bay operations manager, reports an increase in the number of lizards, kākā and invertebrates around Boundary Stream Mainland Island and suggests ‘it’s a bit of a window into what might happen with Cape to City.’

Economic and social benefits

Toxoplasmosis is a disease transmitted by feral cats that causes abortions in sheep, and lamb losses are estimated to cost the region $18 million per annum. The effect of cat control on toxoplasmosis levels in sheep is an important part of the research programme, and is being followed keenly by farmers.

The already successful possum control programme in the region will continue to reduce the risk of bovine TB to cattle and damage to pastures and crops. Landcare Research has completed trials to determine the optimal deployment of ‘chewcards’ across the landscape (see page 17 in this issue) to better identify where to target control efforts to mop up residual possums.

One of the main objectives of the programme is to involve and support the community in biodiversity protection. Landcare Research social scientists have conducted surveys of the general community and landholders to find out why people become interested in native biodiversity and what motivates them to get involved in protecting it. Changes in people’s attitudes to biodiversity and levels of participation are being monitored throughout the programme and compared with areas outside Cape to City. Campbell Leckie, project chairperson, believes the heart of these projects is about people, with each of us having a role to play and making a difference for both our economy and our environment.

The Cape to City project team is also undertaking a biodiversity education programme for schools and educators designed to help students, their parents and teachers understand the value of what is present in the region.

In order for other agencies to emulate the successful components of this programme, Landcare Research is documenting the work as a case study by recording the opinions of the key individuals involved in the various projects within the overall programme.

Grant Norbury, Al Glen, Roger Pech, Andrea Byrom, Campbell Leckie* and Rod Dickson*(Hawke’s Bay Regional Council)