Impacts of mice in Waikato forests

Maungatautari Reserve in the central Waikato is the largest pest-free area in mainland New Zealand, with a 47 km pest-fence excluding pests from 3 300 ha of native forest. In 2008 all 13 species of local pest mammals except mice were eradicated from this wildlife sanctuary. Mice became extremely scarce for a while, but in February 2012 the Maungatautari Ecological Island Trust (MEIT) made the difficult decision to stop targeting them because of the high expense of mouse monitoring and removal in such a large area.

From 2011 to 2016 a diverse team of Landcare Research staff led by John Innes and Deb Wilson studied the density, behaviour and impacts of mice in and about Maungatautari Reserve, so that MEIT, Waikato Regional Council, Waipa District Council, the Department of Conservation and local iwi can assess the risks and benefits of their mouse policy.

Waipa District Council administers the reserve, and Waikato Regional Council has supported the mouse research with funding, over and above its general support for MEIT.

Mouse density in two study blocks

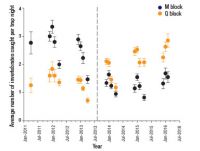

The research team studied the density of mice and their impacts on biodiversity in two adjacent forest blocks: one separately fenced, privately owned site (Q block), where mice reached 20–30 per hectare until they were eradicated in August 2013; and an adjacent part of the main reserve (M block), where mice were initially absent but have increased freely since 2012, a virtual ‘treatment switch’ between sites (Figure 1).

Mouse impacts on biodiversity

The researchers discovered that the main impact of mice was on ground-living invertebrates. There were about twice as many litter invertebrates (all kinds combined) in the block with no or few mice (Figure 2), including twice as many beetles, wētā and spiders, when counted and considered as separate individual groups.

Furthermore, on average, beetles and wētā were about half as large in the block with mice, showing that mice removed many larger individuals. One unexpected result was that there were also significantly fewer earthworms in the leaf litter and surface soil layers when mice were abundant. Mice are known from other studies to eat earthworms that feed on the surface of the soil at night, when mice are also active.

The researchers did not detect any effects of mice on seedlings, land snails or fungi. They showed that mice would eat small bird eggs artificially placed in used nests on the ground, but an attempted study of ‘live’ nests did not find enough of them to resolve whether mice will prey on eggs in these nests. Mice do climb trees, however. Across 20 sites in Maungatautari Reserve, mice were detected in 93% of chew-track devices at ground level, 35% of devices at shrub height (1.6 m above ground) and 17% of devices at subcanopy height (5 m). In a paired trial at nearby Te Tapui Reserve, where all pest mammals in the Waikato region are present, only one mouse was detected at one ground device, while ship rats and possums were found at all levels, including in the canopy (about 8 m).

So what?

The approximate halving of litter invertebrate numbers by mice shows clearly that mice are unhelpful for conservation. This predation reduces the food available for native ground-feeding insectivores such as kiwi. On the other hand, this impact is vastly less than that of the full suite of pest mammals, especially ship rats, stoats, possums and cats. Hedgehogs, in particular, will consume much larger numbers of invertebrates than mice, and even deer and goats are known to reduce litter invertebrates through their trampling.

Mice become very abundant when they are the only mammal in a wildlife sanctuary because they have no mammal predators or competitors. This also has some negative, non-biodiversity outcomes. First, mice may interfere with important monitoring devices set to detect other invading species (should they occur), like ship rats. Second, mice may burrow out of the sanctuary, creating tunnels under the fence that let worse predators like stoats and weasels back in. Third, visitors and volunteers are often unhappy to see mice in a sanctuary they have been told is ‘pest-free’.

The researchers could conceive of only one reason why it may be good to have mice in a sanctuary: mice may in the short term distract larger predators, if any do manage to invade, from feeding on threatened species such as saddlebacks and tuatara. However, it is obviously important that such threatening invaders are rapidly removed.

This research adds to the complex body of knowledge that regional and district councils, wildlife sanctuary trusts and the Department of Conservation use to manage sanctuaries like Maungatautari. The research suggests that while mice are unhelpful for conservation, mice alone are definitely better than having any of the other pest mammals back at Maungatautari. The team hope that control tools will steadily improve, so that in the future mice can be eradicated from large, rugged forest reserves such as Maungatautari.

This work was supported by core funding from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, and Waikato Regional Council.

John Innes, Deb Wilson, Corinne Watts, Neil Fitzgerald, Scott Bartlam, Danny Thornburrow, Mark Smale (Research Associate), Cat Kelly* (*University of Waikato, Hamilton)

Figure 1.Mouse density in the study blocks at Maungatautari, 2011–2016.

Figure 2. Average number of litter invertebrates caught in Q and M blocks.

Researchers developed this chew tag and tracking device that can be pulled up into the canopy to study mouse climbing.