Analysis of home-ranges of pigs assists in their eradication from Auckland Island

Image - iStock.

Pigs have been released on islands worldwide to provide food for castaways, hunters and as livestock. However, they are omnivores and consequently pose a serious threat to native flora and fauna. Pigs can affect the survival and recruitment of native plants through their consumption, rooting up and trampling. They also disperse exotic plant propagules and accelerate soil erosion and consequent sedimentation in waterways. Successful eradication of pigs from islands therefore has potential for high biodiversity gains, but the extreme terrain and/or thick vegetation often found there makes hunting and trapping physically difficult and expensive. There is therefore a growing need to understand the ecology of pigs in different island habitats to increase the efficiency of eradication efforts.

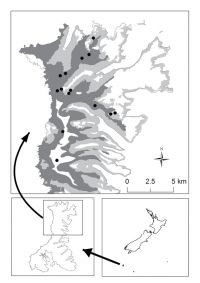

The Auckland Islands in New Zealand’s subantarctic zone is a good example of a very isolated archipelago with terrain likely to make any eradication of pigs difficult. The main Island only is inhabited by pigs, and it is large (46,000 ha), mountainous and located 310 km south of Stewart Island (Fig. 1). The climate is characterised by persistent westerly winds and annual precipitation of approximately 1780 mm. Pigs were introduced in 1807 and were widely distributed by 1880. Dietary studies have suggested they prefer living in the tussock vegetation occurring on higher land and potentially migrate to the coast in winter. Both of these behaviours may make eradication easier.

Dean Anderson used Department of Conservation location data from Argos telemetry collars deployed on 15 pigs on Auckland Island to address two objectives:

- To quantify home-range sizes across sex-age classes, and examine how these vary with vegetation cover; and

- To develop a resource-selection model that describes how pigs select various attributes of the environment.

Dean’s analyses showed that home-range size varied from 1.37 – 32.8 km2 (mean = 10.05 km2, SD = 9.0 km2). The mean range sizes for males and females were 10.93 km2 and 8.89 km2 respectively, but the difference was not significant. Home-range size increased with increasing tussock cover. While home-range centres are not an indicator of home-range use, they were all located in or next to tussock cover (Fig. 1), suggesting a preference for this habitat, perhaps due to ease of movement relative to that in scrub.

A hierarchical Bayesian analysis of resource-selection showed that pigs generally do not migrate to the coast in winter as previously thought (although one pig did so in June; see Fig. 2). Results also demonstrated a strong attraction for tussock cover and for north-facing slopes, and repulsion from scrub vegetation. The pigs had the tendency to make direction reversals in 1-day time intervals, which resulted in a criss-crossing pattern of home-range use, rather than directional persistence around range edges. The Bayesian approach also allowed Dean to account for the varying levels of telemetry error among the location data, and permitted the use of all the data and more accurate inference of the results.

It is clear from this analysis that eradication operations of pigs on Auckland Island need to put all the animals at risk by seeking them out, rather than waiting for them to come down to the coast. Because of access issues, this is a difficult task, but one that can be made less arduous by focusing efforts in tussock vegetation and to a lesser extent on north-facing slopes. If traps are used, they can be spaced further apart in areas with high tussock cover (where their ranges are greater) than in areas with low tussock cover. Hunters should use the knowledge that the different ranging patterns in tussock and scrub cover will influence the density of their ‘sign’. Further, the tendency of pigs to make direction reversals with one-day time intervals rather than roaming along home-range edges with directional persistence may be of assistance in planning for their eradication. However, Dean believes these patterns of movement and habitat use are likely to change as the population declines and as the pigs become wary of hunters and trapping devices. As the pigs adapt to the pressure of the eradication efforts, control staff will have to adapt to altered patterns of pig movements.

This work is funded by the Department of Conservation.

Dean Anderson

Pete McClelland & Liz Metsers (Department of Conservation)

Fig. 1. The study location on Auckland Island. Tussock and scrub habitat are depicted as dark and light grey respectively. All other land covers are grouped together as white. Black dots show the home range centres of the radio-collared pigs.

Fig. 2. The movements of one pig showing clear selection for tussock vegetation (tussock = dark grey; scrub = light grey; and alpine = white). This animal unusually also demonstrated a movement toward the coast followed by moves inland.