Wētā tracking - how do we know when translocations are successful?

Translocations are proving crucial for the survival of giant wētā species as habitat destruction and predation continue to impact our most iconic native invertebrates. Compared to large threatened fauna, such as native birds, insects like wētā are very difficult to monitor when at low densities.

How do we know when translocations of wētā have been successful? In the past it has appeared that some transferred populations of insects have failed to establish in their new habitats, but with wētā females producing about 200 eggs per year, there can be exponential growth in wētā numbers at a new site after about ten years.

A decade is a long time in threatened species management. The Department of Conservation (DOC) and sanctuary managers need earlier indications of success to guide future funding and other decision making.

New insights into wētā movements

We have pioneered the use of footprint tracking tunnels and extended the use of miniature radio transmitters to study and monitor translocated wētā populations.

We have pioneered the use of footprint tracking tunnels and extended the use of miniature radio transmitters to study and monitor translocated wētā populations.

Radio transmitters were fitted to Cook Strait giant wētā (Deinacrida rugosa) released at Zealandia at Karori, Wellington. Radio tracking monitored the establishment of the animals and also provided insights into the behaviour of wētā, including the remarkable finding that males were travelling up to almost 300 metres each night, well over double the distances covered by female wētā.

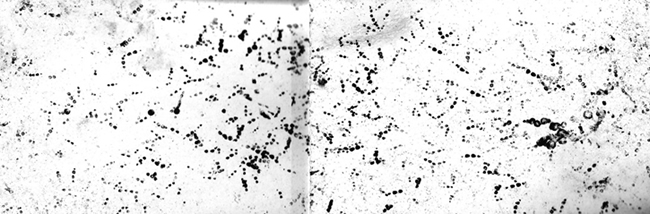

The use of tracking tunnels, normally used to monitor the presence of small mammals, stemmed from the discovery that wētā left footprints in tunnels being used to detect the presence of vertebrate pests. Scientists have since found that wētā are equally fond of the peanut butter-based bait used to lure rats and mice into a tunnel, which has an ink pad with pieces of white card either side.

The tracking tunnels have been used extensively at wētā translocation sites. Researchers checking the tunnels have found up to three wētā lined up behind the entrance of an occupied tunnel, like cars at a takeaway restaurant drive-through.

We have worked closely with DOC and several mainland sanctuaries over the use of wētā tracking tunnels.

Footprint tracking has proved the success of an initiative to save the Mercury Islands tusked wētā (Motuweta isolata) from extinction. In the 1990s there was a dramatic decline in the only known population of the species on Ahu or Middle Island off the eastern Coromandel Coast. From one male and two female wētā, Landcare Research developed a captive breeding programme and raised 567 individuals for release on six nearby, mammal-free islands.

|

| Weta footprints recorded in a tracking tunnel. |

Seven years on from the first releases, populations have established on four of the islands, and footprint tracking is now proving the most effective method of monitoring. On one island, Red Mercury Island, footprint tracking has highlighted how the population is expanding outwards from the initial release site by 100-150m per year.

Back on Middle Island, tracking tunnels have failed to detect any Mercury Islands tusked wētā in the past five years, leading researchers to believe the breeding programme and translocations probably saved the species from extinction.

At the DOC-managed Matiu-Somes Island in Wellington Harbour, tracking tunnels have highlighted a surprising shift in the Cook Strait giant weta population predominantly from one end of the 25 ha island to the other. Scientists now hope to get a better understanding of why the wētā are on the move.

At the privately-managed Maungatautari Ecological Island in Waikato, footprint tracking tunnels have highlighted the success of a mammal pest eradication programme by showing dramatic increases in wētā tracking rates after the control work.

Effective monitoring tool

While there is growing public interest in conservation, and in particular the survival of our threatened native flora and fauna, funding for biodiversity management remains tight. Practitioners working to save our iconic species need effective and cost-efficient monitoring tools like tracking tunnels.

When Mercury Islands tusked wētā were first released on neighbouring Coromandel islands the only way to monitor the released animals was to scrape away the leaf-litter and soil to reveal wētā in the underground chambers.

Now tracking tunnels are the tool of choice for monitoring these and many other wētā populations. Placing, checking and re-baiting tunnels is a quicker, less expensive and easier way to monitor the presence of wētā, and avoids damage to the animals’ burrows.

This new approach is also providing better quality information about weta movements and new insights to assist in the management of these fascinating little giants.

“For DOC, the footprint tracking tunnels developed by Landcare Research have revolutionised the monitoring of some threatened weta species, including arboreal species,” says DOC Senior Science Adviser, Eric Edwards.

“Footprint tracking tunnels are also excellent for detecting when weta are present when at such low densities that they are undetected by other methods,” says Eric. “They are already widely used by field workers to monitor rodent predators because of their simplicity, so they have the added advantage of simultaneously monitoring both the weta and their predators.

“The only challenge can be that different weta species have similar footprints so tracking tunnels can only be used to monitor adults of the largest species at a locality. This is usually not a problem when monitoring threatened weta because they are generally the largest species present.”

Recent genetic work undertaken by Landcare Research has revealed inbreeding depression within translocated populations of the four northern species of giant wētā. This research will guide the management of giant wētā taxa, particularly in determining the number of individuals required for establishing genetically-diverse populations in future translocations.